Wood Bison Versus Plains Buffalo

by Francie M. Berg

Wood Buffalo bulls tend to be taller and more square at the hump than Plains Buffalo. Historically, they lived in the boreal forests of Northern Canada and Alaska where snow is deep and long-lasting. Parks Canada.

Wood Bison are the largest land mammal in North America.

Adult males stand 6 feet tall at the shoulder and measure 10 feet long.

This is about one-third larger than the Plains Buffalo.

The Wood Buffalo are also considerably heavier.

Parks Canada maintains a bison weight database going back to 1956.

During all that time, the records show only one Plains Bison bull that weighed more than a ton (2000 pounds or 909 kg).

At the same time–when fully grown—one-third of the Wood Bison bulls exceeded this weight.

Wood Buffalo females are considerably smaller than bulls, generally weighing around 1,200 pounds.

Wood Bison are about 15 percent heavier than Plains Bison.

Original distribution of Wood Bison during the last 5,000 years (stippled). Based on available zooarcheological and paleontological evidence and oral and written accounts. Parks Canada.

Scientists say the larger size is an adaptation to the more extremely long-lasting and cold climate of the far north.

Historically, Wood Bison range extends through the boreal forests of Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and much of the Northwest Territories, Yukon, and Alaska, as in the above map.

Boreal forests are defined as forests growing in high-latitude environments where freezing temperatures occur for 6 to 8 months and in which trees are capable of reaching a minimum height of 5 m and a canopy cover of 10 percent.

The Wood Bison is often distinguished by his taller, more box-like hump that has its highest point well ahead of his front legs.

Parks Canada suggests this kind of hump has evolved in the Wood Bison to support a more massive muscle structure that helps them sweep their head through deep northern snows to provide more access to the grasses and sedges beneath the snow in a long winter.

By contrast, the highest point of the Plains Bison’s hump is directly above the front legs, with the hump more smoothly rounded.

This accomplishes the same result—as a structure to sweep away snow. However, the snow tends not be as deep, long-lasting and formidable in their usual range as that which hits farther north.

Below are noted distinctions between Wood Buffalo and Plains Buffalo as presented by Parks Canada.

The highest point of the hump is well forward of the front legs on Wood Bison. Cape blends smoothly toward the rear. Parks Canada, used with permission.

Wood Bison

Highest point of hump well forward of front legs

Virtually no chaps on front legs

A thin scraggly beard

Neck mane short, does not extend much below chest

Cape grades smoothly back towards the loins with little if any demarcation

Forelock lies forward in long strands over forehead

Hair usually darker, especially on head

Smoother, more rounded hump, centered over front legs. More pronounced cape ends at shoulder. Parks Canada.

Plains Bison

Highest point of hump is directly over the front legs

Large thick chaps on front legs

Thick pendulous beard

Full neck mane extends below the chest

Sharply demarcated cape line behind the shoulder

Thick bonnet of hair between the horns

Cape usually lighter in color

About one-third smaller than a Wood Bison

In addition to size and hump distinctions the differences between Wood and Plains Bison can be separated into pelage and structural characteristics.

The Wood Bison is distinguished by darker color, absence of chap hair on the front legs, and a less distinct, but darker cape of the shoulders, hump, and neck region that grades smoothly back onto the loins.

They have a thin pointy beard; shorter and less dense hair on the top of the head, around the horns, and beard. A skimpy neck mane and longer and more heavily haired tail.

Their head is large and triangular, with large shoulders and long dark brown and black hair around head and neck.

Males possess short, thick, black horns that end in an upward curve, while females have thinner, more curved horns.

Wood Bison vocalizations are also different from the sounds made by Plains Bison. And the Wood Bison’s social interactions during the rut tend to be less violent.

Hardy from birth, Wood Bison calves can stand when they are only 30 minutes old and run alongside their mothers within hours of birth.

Plains Bison tend to have hair character which is lighter, larger and more obvious—with more variation in color. A yellow-ochre cape spreads over the shoulders and ends with noticeable separation in texture and color.

They grow a thick bonnet of hair between the horns, covering the lower horns, and a full neck mane extending below the chest.

The Plains Bison sport a full beard and large chaps on the front legs, and the tail is short and thin.

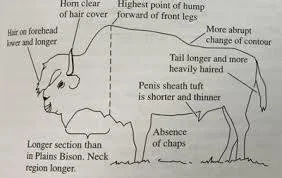

For their part, the National Park Service in the United States offered these 2 sketches in a Bison Bellows feature in April 2018.

Wood Buffalo sketch reveals differences with Plains Buffalo. Courtesy van Zyll de Jong et al. NPS.

Wood Buffalo

Highest point of hump forward of front legs

More abrupt change of contour along back

Tail longer and more heavily haired

Penis sheath tuft shorter and thinner

Horns clear of hair cover

Hair on forehead lower and longer

Neck region longer than in Plains Bison

Absence of chaps

Plains Buffalo sketch shows more long hair cover in front parts of animal. Courtesy van Zyll de Jong et al. NPS

Plains Buffalo

Highest point of hump over front legs

Declining back slope

Tail shorter and thinner

Penis sheath tuft longer and thicker

Horn often covered by dense hairs

Yellow-ochre cape

Sharp separation from cape in texture and color

Chaps (skirt)

Larger beard

Two Subspecies Recognized

Wood Buffalo prefer boreal forests of Canada. They are largest land mammal in North America. Parks Canada.

Modern American buffalo are identified in 2 subspecies well suited to their respective environments.

The prolific Plains Buffalo grazed throughout the open country and the shy Wood Buffalo clustered in small groups in forest and mountain terrain, especially favoring the far north.

Under scientific classification, the American Plains Buffalo is listed as genus Bison, species bison bison, and subspecies Bison bison bison.

The Wood Buffalo is Bison bison athabascae, named for an Indian word, a lake.

“Athabascae” recognizes the Cree native name for the large Lake Athabasca and surrounding watershed in Canada. Athap-ask-a-w means grass or reeds here and there.

Interestingly, early scientists of the 19th century marked these differences and gave the two subspecies their scientific names.

It was thought that Wood Buffalo were “the finest specimens of their species, superior in pelage, size, and vigor to those of the Plains whose descendants today exist in our parks.”

Then came a time of debate. Many argued the differences were not genetic, but simply a function of the environment where they live.

However, a large-scale study in the early 1990s analyzed Canadian data and found the two subspecies maintain their respective traits regardless of where they live and what they eat.

More recent research at the University of Alberta reveals genetic differences, thus supporting those early scientists. Sufficient difference was found between Wood Bison and Plains Bison, it was thought, to warrant two different subspecies names.

Yet scientists have discussed through the years whether the two subspecies are simply ecotypes.

In other words, if Wood Bison were placed in Plains Bison habitat, or vice versa, might they eventually assume the traits of typical Bison there, simply due to environmental pressures?

Subspecies Still Questioned

Science, of course, is always open to revision.

Not all scientists agree with the subspecies designation.

One who disagrees is Matthew Cronin, University of Alaska Fairbanks professor of animal genetics. He is based at the Matanuska Experiment Farm in Palmer.

In 2013, Dr. Cronin and colleagues studied 65 Wood Bison from 3 herds and 136 Plains Bison from 9 herds in Alaska, Montana, Utah, Wyoming, New York, Alberta and the Northwest Territories, along with a database of differing cattle breeds.

The Cronin findings are published in the online May 10, 2013 issue of the Journal of Heredity. http://jhered.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2013/05/09/jhered.est030.abstract?sid=6fde43b1-288b-4d53-adae-61cc2628db1e

Cronin pointed out that the term subspecies denotes a formal category and that evolutionary history is a primary criterion for subspecies designation.

For instance, European cattle and tropical cattle have separate origins, are genetically distinct and thus have a scientifically supported subspecies designation, he says.

“This creates a paradox for biologists because subspecies can be designated by one author, rejected by another and still others reject the entire subspecies ranking.”

He contends that Wood and Plains Bison originally had ranges adjacent to each other, rather than separate origins.

Therefore they should be considered differing geographic populations, not subspecies.

He notes that some Plains Bison are more genetically different from each other than they are from Wood Bison.

Despite Cronin’s evidence, Parks Canada and conservation groups in Alaska operate under the guideline that Wood Bison are a distinct and separate subspecies and ideally, should not be hybridized with Plains Bison.

Spokesperson Cathy Rezabek says that US Fish and Wildlife contends the two groups of bison are separate.

“We based our finding on the scientific information available, which indicated that there has been historical physical separation in their ranges, as well as behavioral and physical differences and genetic differences. “

“Worth preserving whether or not they are formally recognized as a subspecies.” At Elk Island Park the two subspecies are kept separate.

In this light, bison conservationists agree on several things, she noted:

1) Multiple morphological and genetic characteristics distinguish Plains Bison from Wood Bison;

2) Wood Bison and Plains Bison continue to be morphologically and genetically distinct, despite some historic forced hybridization; and thus

3) Wood Bison constitute a subspecies of bison, and therefore, should be managed on a par with Plains Bison.

An eminent Canadian wildlife biologist once observed that “debating taxonomy does not absolve humans of the responsibility to protect intra-specific diversity as the raw material of evolution.”

Another suggests that the Wood Bison population is in a class by itself, “Worth preserving whether or not they are formally recognized as a subspecies.”

Therefore, park authorities keep separate the two subspecies to retain their natural traits.

Originally published December 1, 2020 on Buffalo Tales and Trails