Buffalo vs Bison– What Shall We Call Them?

April 12, 2024

What shall we call this magnificent monarch of the Plains—buffalo or bison?

Some people are adamant: the term buffalo correctly refers only to water buffalo in South Asia and Cape buffalo in Africa. We are simply wrong, misinformed, or ignorant to even think of calling the American bison—Buffalo.

by Francie M. Berg

First published May 5, 2020

What shall we call this magnificent monarch of the Plains—buffalo or bison?

Some people are adamant: the term buffalo correctly refers only to water buffalo in South Asia and Cape buffalo in Africa. We are simply wrong, misinformed, or ignorant to even think of calling the American bison—Buffalo.

Amy Tikkanen, writing in the Encyclopedia Britannica lays it all out. In her world it comes down to “Home, Hump and Horns.” Bison have one set, and buffalo the other.

But not so fast.

Many people who know the science simply prefer the term buffalo. I think most of us in the west—where the buffalo still roam in rather large numbers—do prefer it.

It rolls off the tongue in a friendlier way.

Yes, in scientific usage we agree, it is bison—as is bovine, equine and canine.

My husband Bert, a veterinarian, often used those terms when explaining treatments.

But do we call the cow, horse or dog those scientific names—bovine, equine and canine—in everyday talk?

One happy dog—or is he a friendly canine? Photo by Eric Ward.

Of course not. We don’t even think of them, our beloved friends, that way, do we?

Historic use of Buffalo in America

The word Buffalo actually came from early French fur traders and trappers who called the animals les boeufs, a Greek word for “the beeves” meaning oxen or bullocks.

In that context both names, bison and buffalo, have a similar meaning.

Buffalo has a long history of being used in North America, dating from 1625 when first recorded—even before bison was first documented, in 1774.

Buffalo even has a verb form—to buffalo, meaning to overawe or bewilder.

Here in the west we are well aware that a number of our other species were misnamed by early visitors.

Like buffalo, these early names often stuck, and have become generally accepted into our language, even though they may not derive from their proper scientific origins.

For instance, our antelope is really a pronghorn. An American jackrabbit is a hare, not a rabbit.

Our elk is really a wapiti, while our moose is the same as the European elk. And American caribou are identical to domesticated reindeer in Europe and Siberia.

But that’s okay—we like it this way.

The American Bison Association has made attempts to persuade buffalo ranchers to call their livestock bison. It does seem to work well when ranchers sell meat.

Maybe we all need a bit of distance for that.

That’s not the issue.

Otherwise, calling them Bison seems to put these magnificent, iconic animals out there at some distance. There’s no heart in it.

In contrast, Buffalo seems a good, solid, friendly yet respectful name, with no formality separating us from these majestic animals.

You can put some love into it if you choose.

“Give me a home where the Buff-a-low roam, where the deer and the antelope play.”

“Buffalo gals gonna come out tonite–come out tonite–and dance by the light of the moon!”

Can’t do that with Bison.

That’s not really the issue, though.

“Oh, give me a home where the buffalo roam,” a song for all ages. Photo by Akshar Dave.

“Buffalo gals gonna come out tonite–come out tonite–and dance by the light of the moon!”

Can’t do that with Bison.

That’s not really the issue, though.

Confusion of ‘Home, Hump and Horns?’

I think we can all agree that the Encyclopedia Britannica item as written by Amy Tikkanen, sets the argument out scientifically and clearly. No wiggle room there.

“It’s easy to understand why people confuse bison and buffalo,” Tikkanen writes. “Both are large, horned, oxlike animals of the Bovidae family. There are two kinds of bison, the American bison and the European bison, and two forms of buffalo, water buffalo and Cape buffalo.

Water Buffalo live in South Asia. They tend to have large horns—with wide graceful curves—no hump. Photo by Lewie Embling.

“However, it’s not difficult to distinguish between them, especially if you focus on the three H’s: home, hump, and horns.

“Contrary to the song ‘Home on the Range,’ buffalo do not roam in the American West. Instead, they are indigenous to South Asia (water buffalo) and Africa (Cape buffalo), while bison are found in North America and parts of Europe.

“Another major difference is the presence of a hump. Bison have one at the shoulders while buffalo don’t. The hump allows the bison’s head to function as a plow, sweeping away drifts of snow in the winter.

“The next telltale sign concerns the horns. Buffalo tend to have large horns—some have reached more than 6 feet (1.8 meters)—with very pronounced arcs. The horns of bison, however, are much shorter and sharper.

“Despite being a misnomer—one often attributed to confused explorers—buffalo remains commonly used when referring to American bison, thus adding to the confusion.”

Of course, Britannica is British, lecturing us a bit on our use of the English language. That’s okay, we can take it.

Confusion is not really the issue either. Neither is science—we understand and accept that.

The thing is, we just like the buffalo. And we like to call them that. It fits.

A ‘Harmless Custom’

William T. Hornaday, that great historian of the species, was good-humored about it. He called the animals, Bison in his own writings. Nevertheless, he wrote in 1889:

“The fact that more than 60 million people in this country unite in calling him a buffalo, and know him by no other name, renders it quite unnecessary to apologize for following a harmless custom which has now become so universal—that all the naturalists in the world could not change it if they would!”

Professor Dale F Lott, University of California scientist, puts it even better, I think. He’s not confused about anything– most especially his beloved buffalo!

Born on Montana’s National Bison Range, where his grandfather was Superintendent, he grew up seeing buffalo on the hills every day. His father, from a nearby ranch, worked on the Bison Range—and had married the boss’s daughter.

Professor Lott, who in my opinion surely loved and understood the buffalo as much, if not more, than any other scientist who wrote of them, explains why he uses both terms interchangeably.

“I’ve given a lot of thought to whether I should call my protagonist bison or buffalo,” he explains in the preface to his book: American Bison: A Natural History.

“I decided to use both names.

“My scientist side is drawn to bison. It is scientifically correct and places the animal precisely among the world’s mammals.

“Yet the side of me that grew up American is drawn to buffalo—the name by which most Americans have long known it.

Buffalo honors its long, intense and dramatic relationship with the peoples of North America.”

Lott leaves the discussion there. Enough said.

Ervin Carlson, former Director of the Blackfeet Buffalo Program on the Blackfeet reservation in Northwestern Montana, and past President of the Intertribal Buffalo Council, has put some thought into this issue, too.

He says his people do not call thes animals Bison.

“We think of Bison as a white man’s term.

Ervin Carlson, former president of the InterTribal Buffalo Council, which assists tribes in returning buffalo to Indian country, surveys a new herd released on Cherokee Tribal land in northeast Oklahoma on Oct. 9, 2014. The buffalo were brought from South Dakota by cattle truck. Photo by Jim Beckel, The Oklahoman.

“They were everything to us—we survived on them.”

And when the buffalo suddenly vanished, many of the Blackfeet people starved to death. Of course, they have the right to call these beautiful creatures Buffalo!

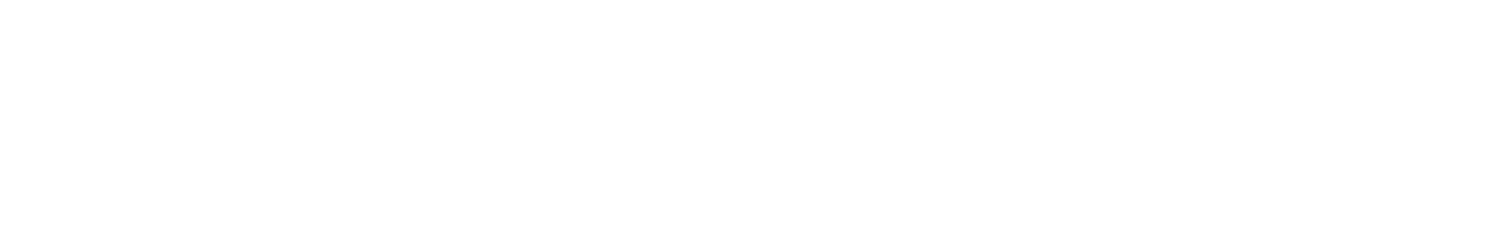

No less an authority than the National Geographic Magazine, which has published many buffalo articles over the years, has declared the terms Bison and Buffalo interchangeable.

In a recent article on the western lands buffalo controversy, National Geographic stated flatly, “Historians estimate there were tens of millions of bison—the term is interchangeable with buffalo—when Lewis and fellow explorer William Clark traversed the northern plains.” (Feb.2020, p75)

Buffalo is defined in that magazine’s Style Manual as, “Singular and plural. Acceptable synonym for bison, which is the scientifically correct designation.”

Apparently, this means that it got the green light from the style committee, which had given it a close review.

National Geographic in its Feb 2020 issue–on the controversy of the American Prairie Reserve land purchases in central Montana—declares the terms Buffalo and Bison interchangeable. Photo by F. Berg.

Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary accepts three categories of “buffalo.” Screenshot.)

Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary also accepts both terms, and in one definition defines buffalo as “any of a genus (Bison) of bovids: especially: a large shaggy-maned North American bovid (B. bison) that has short horns and heavy forequarters with a large muscular hump.”

It also defines the term as “the flesh of the buffalo used as food.”Native Americans often prefer to use buffalo names in their own languages when talking with each other, such as the Lakota terms, Tatanka and Pte.

Other people play with the pronunciation a bit.

Fans of the North Dakota State University Bison football team, winner of 16 national championships and having won its past 36 games, the longest streak in FCS history, have their own style of cheering—roaring—with a “Z” sound.

That ”Z” chant resounds throughout football stadiums across the land—as in “Go Bizon.”

‘Buffalo Honors a Long, Intense Relationship’

So, when it all shakes out, what should we call them? These majestic, magnificent creatures of the Plains and Prairies?

My answer is this—a consensus of those I call experts:

Call them whatever you like, the term with which you are most comfortable—or use both interchangeably.

Maybe Buffalo when you’re with friends—or Bison.

Bison when you’re with scientists—or Buffalo.

Whichever feels right to you. But as Hornaday suggests, don’t apologize.

It’s a mistake for Americans to think we “should” call our own Greatest Mammal whatever others tell us we should.

We can say, cheerfully, with a smile, no trace of rancor, “No, I don’t think so.”

To many of us, they are simply buffalo.

This is the name that honors the majestic animal we know.

Buffalo celebrates that “long, intense and dramatic relationship” they have with the Native people and settlers of North America.

And that’s the issue.

Welcome to Buffalo Tales and Trails!

November 15, 2023

Today, buffalo live in all 50 states and across Canada, and serve as a symbol of American unity, resilience and healthy lifestyles and communities.

by Francie M. Berg

First published April 28, 2020

Welcome to our first issue of Buffalo Tales & Trails! Everything you ever wanted to know about buffalo!

Thanks for your interest in buffalo! We are bringing you a combination blog and website.

My assistant Ronda Fink and I have produced books and websites, but never before a blog. So this is more than a first issue—it’s a new venture for us!

But not a new topic. Buffalo are old as the hills in the northern plains. We know them. Yet they are still surprising us with their wild nature and amazing capers.

Our mission is first of all—to help young people get to know and love the magnificent buffalo/ bison—America’s new National Mammal! This means teachers need to be involved.

So this is first of all for teachers and their students! Especially Native American students who have a special awe and pride in their buffalo.

And of course, we invite everyone who has a soft spot in your heart for buffalo. Come along on this incredible journey. We won’t let you down!

You can be an expert of sorts on this very specific subject. It’s a fun topic.

The American Bison became the official National Mammal of the United States on May 9, 2016, when President Obama signed the National Bison Legacy Act. Photo courtesy of SD Game, Fish and Parks, Chris Hull, photographer.

It’s a great milestone for an animal that played a central role in America’s history and culture, helped to shape the lifestyle of Native Americans on the open Plains, and then declined within a hair breadth of becoming extinct.

Today, buffalo live in all 50 states and across Canada, and serve as a symbol of American unity, resilience and healthy lifestyles and communities.

My name is Francie M. Berg. I didn’t know much about buffalo when my husband, a veterinarian, and I moved our family to Hettinger, North Dakota.

Sure I’d seen them in herds here and there, grazing up a green coulee or standing sleepily in a corral.

Much like cattle, I thought. As I said, little did I know.

Where the Buffalo stories Come Together

Then I discovered we’d come to the place where all the buffalo stories come together, now and in the distant past. It happened right here on the western border between North and South Dakota.

This area of the Northern Plains was home to buffalo from ancient times.

Here early hunters, with no horses or guns, ran buffalo off the Shadehill buffalo jump as long ago as 7,500 years, according to archaeologists from the University of North Dakota, among others who checked this out.

The buffalo left the Dakotas in the 1860s, as settlers moved in.

But then the very last wild herd of 50,000 buffalo migrated here in 1880.

That was followed by the last great buffalo hunts—traditional Native hunts with due ceremony. We have first-hand accounts from the hunters themselves.

The last great buffalo hunts were here—traditional Native hunts of the last wild herd of 50,000 head. Buffalo Hunt, by Alfred Jacob Miller 1838. Amon Carter Museum.

Hey, how come no one knows about this? Why isn’t it in the history books?

Then, when they faced extinction, 5 buffalo calves were rescued here on the South Grand River and nourished by a Native American family, the Duprees, who gained international fame for helping to save the species.

They multiplied and today buffalo and deer again roam in our rugged buttes and badlands, forest service lands and grassy plateaus—lands that look much as they did 150 years ago.

Paying more attention, I listened to the stories, read a few more buffalo books. It was an awakening for me.

Wow! These are not cattle! Actually, more like wild animals—deer caught in the headlights.

Buffalo are not cattle! More like wild animals, like deer caught in the headlights. Photo by Denise Anderson, Bismarck.

I’ve been collecting buffalo stories ever since.

For over 35 years I’ve been researching buffalo, reading every source I could find, visiting public, commercial and tribal herds, talking with down-to-earth bison ranchers from across the country, scrambling in the rocks above some of the most famous buffalo jumps in the Rocky Mountains, and writing three books about the majestic buffalo.

We now have a historic tour of 10 famous buffalo sites for you. More about that later.

People tell me that the more you get to know buffalo, the more you love them. It’s true, I’ve found.

Yes, along the way, it seems, I’ve been smitten by these magnificent animals. We’re so glad to have you along for the ride! And we think you might develop a passion for these majestic animals, too.

Getting to Know you, Our Readers

We want to get to know our readers. You and your family and your friends.

You can help us find the best buffalo stories. There are many.

We’ll also explore the science. Together we’ll venture along new trails. Dare to take least-travelled roads. Ask the perplexing questions.

With your help, we’ll cover a wide spectrum of buffalo lore and learning, and entertain you along the way.

And, yes, please warn us if we seem about to fall off a buffalo jump—or take a disastrously wrong turn . . .

1. First of all, we hope many of our readers are TEACHERS—you smart, busy people, always looking out for new and interesting ways to interact with students. We’re here for you.

2. We also hope to have your Students on board, especially Native American Youth, with your special awe and pride in buffalo.

3. Younger Kids, too—we’ll find some fun videos for you.

Back to school. How about a buffalo story? Photo by Kuanish Reymbaev

4. Also, please join us, Bison Experts—Scientists, College Professors, Forest

Rangers and Native Tribal buffalo managers. You wonderful people. We’re here to learn from you. Please don’t leave us. After all, you might be an expert who—once in awhile—just needs to smell those wild roses blooming along the buffalo pasture fence? We’ll help you!

5. Then of course, we want the Moms and Dads to join us—you busy, busy people,

pulled 6 ways from Sunday, a dozen new stresses every day. We wish you the peace and pleasure of contemplating a buffalo herd right here, online if not for real. You deserve the tranquility of enjoying an engaging buffalo photo or story for a few minutes

6. Also, we plan to have real Buffalo Ranchers on hand, you bold and adventurous women and men—who know your buffalo—and will tell us some of your wonderful stories. (And if we visit, maybe you’ll share a bowl of your delicious buffalo stew with us! Mmmm!) It’s been said, “Everyone who works with buffalo has a story.” We invite you to tell us a few of your own.

Buffalo ranchers Steve and Roxann McFarland work buffalo in the chutes on a cold January morning on their ranch southwest of Hettinger. Photo by Francie Berg.

7. Oh, and we’re not forgetting Grandmas and Grandpas! Looking for a bit of fun and new experiences when you open your computer? Maybe you live alone and it gets lonesome at times, doesn’t it? Need a friend? We promise you’ll meet herds of four-legged friends right here. But a word of caution, don’t expect the cuddly kind of friends! What we’ll bring you are sound and solid, four-feet-on-the-ground, no nonsense, but near-wild animals, who will gain your respect, and I think, in time, your affection.

And some fun stories too!

Enjoy the journey!

Want to Raise your own Buffalo Herd?

Wouldn’t that be fun!! Your own buffalo herd!

My Veterinarian husband—a practical man who soon gained buffalo experience—nixed that idea every time I brought it up.

But there are many hobby buffalo farmers around. If you yearn to have your own buffalo, say, a bull and 2 cows—well, many buffalo ranchers, big and small, started in just that way.

“Buffalo are like rabbits! If you’re not careful, pretty soon you’ve got too many!” A Wyoming rancher warned her friends after watching their herd grow from 1 bull and 2 heifers to 500 animals—outgrowing their pastures. SD Tourism.

They called it a “hobby herd.”

It’s not an entirely bad idea.

Just watch a group of Native American boys and girls visiting their own tribal herd. Note the pride and awe in their eyes, their silence and whispering voices, and you’ll have an idea of the respect these animals command, just by being themselves.

But watch out! Be warned of two things: they multiply and they’re not as gentle as they look.

“Buffalo are like rabbits! If you’re not careful, pretty soon you’ve got too many.” That’s what Toots Marquis, a woman rancher from Gillette, Wyoming, warned her friends.

The grandfather in her family bought a buffalo bull and two heifers, just for the novelty of it, to run with his cattle.

A group of Native American boys and girls from the Oneida Tribe in Wisconsin get a rare close-up view of their tribal herd on a field trip. Courtesy of Oneida Tribe.

In what seemed like only a few years, they multiplied to 500 animals. By the time Marquis was left in charge by herself, she struggled to cull them back and keep the herd at around 75.

And don’t imagine that buffalo are going to be nice and cuddly.

Even playful calves bucking through a herd—don’t think you’ll join them. There’s more than one hostile mother watching, possibly all set to charge.

Don’t even think of posing for a selfie by edging close to a lethargic-looking bull. Remember the warnings, you’ll need something large—like maybe a pickup truck—between you and that big guy, just standing there watching you with what, deceptively, looks like sleepy eyes.

Their sleepy demeanor has fooled many. That bull can spin on a dime and run 40 miles an hour!

Can you? If not, then look out!

One day in 1906, a group of Mexican dignitaries came up the Missouri River in a tour boat to see Scotty Phillip’s buffalo herd in the badlands. They laughed at the big bulls, and boasted—with a bit too much exuberance—that their feisty Mexican fighting bulls would make short work of those lazy, slow moving bulls.

They challenged a bull fight—but that’s another story. We’ll tell you about the Mexican bull fight in Juarez another time (or you can read about it in Buffalo Heartbeats on page 182).

Then there are the fences. Are yours high enough? Strong enough?

You don’t have to own buffalo to enjoy them, of course. You can see them in many state and National Parks in the US and Canada.

In fact, I’m pretty sure everyone who has a passion for them might need to contemplate a live buffalo herd occasionally for a good measure of that peace and tranquility.

People tell me the more you get to know buffalo, the more you will love them. SD Game, Fish, Parks, photo by Chris Hull.

Don’t worry. Most of us can find buffalo around—in public zoos and parks, or private herds that you might view from the road, or nearby tribal herds which you can arrange to visit.

You might be surprised at the bison opportunities near where you live right now. If not, please come to see us on the Northern Plains, or contact your nearest Indian Reservation. They enjoy showing their buffalo herd to visitors.

Happy National Bison Day!!

OctobeI 25, 2023

t’s coming up! Buffalo Day is November 4, 2023—Always the first Saturday in November. Get your family ready to celebrate! Remember, in the US and Canada we use the terms Bison and Buffalo interchangeably. And that’s OK. Either fits!

by Francie M. Berg

It’s coming up! Buffalo Day is November 4, 2023—Always the first Saturday in November. Get your family ready to celebrate!

Remember, in the US and Canada we use the terms Bison and Buffalo interchangeably. And that’s OK. Either fits!!

Some would have us use only the scientific name, Bison. But just think how many cities and towns, counties, creeks, rivers and majestic buttes across this North American continent are named for Buffalo! Would the so-called “experts” have us change them all? Impossible, of course. And how petty to be so limited in our vision!

We’ve been using that term since 1616 when the French explorer, Samuel de Champlain, used it to describe the animal. A few years later, in 1625, Buffalo first appeared in the English language in North America, from the French word, boeuf, a Greek word given to Buffalo by French fur trappers here. Not until 1774—a century and a half later—was Bison first recorded to refer to these mammals in a scientific sense. So are we OK with that?

“We want to go full Buffalo and embrace their unique appearance, calming personalities and utterly cute shapes. Get ready to learn more about them and why we should all try and be more like bison,” says one Buffalo Aficionado.

Anyway,—no apologies. Use whichever you prefer. (Except of course in a scientific discussion.)

How will You Celebrate?

1. Wear a Buffalo T-shirt

Select a T-shirt that shows your love of bison—and wear it proudly! Your kids will enjoy a new Buffalo shirt if they don’t have one! So will Grandpa and Grandma.

2. On National Bison Day—Change your profile picture to Bison

On National Bison Day—November 4, 2023—Change your profile photo on social media to a Buffalo silhouette. It’s an annual event that falls on the first Saturday in November. All Americans can reflect on the impact bison have as a part of our environmental and cultural heritage.

Keep it up for a full month! November is Native American month--you can honor Native Americans at the same time with a nice Buffalo photo. Buffalo are especially revered by Native people—They’ve been central to their survival for centuries as both food and spiritual inspiration.

3. Visit a Buffalo herd

A vast number of wildlife parks, tribal herds and buffalo ranches showcase Buffalo across the US and Canada. Find out if any are located close to where you live. Your children will be delighted to experience the wonder of our latest national icon—the Bison, or Buffalo!

However, take care! Don’t get too close—75 feet or more is recommended! Buffalo are stoic—but don’t try to push them around!

4. Plan a Party

Celebrate with a family party, kids party, young adult party or just friends getting together.

Buffalo are easy to draw. Design and paint or color a stand-up place card for each guest. Or design some dark brown bushy beards. Tie them on your guests with a shoestring around the ears. Know any Buffalo games?

5. Eat some Bison—yum, yum! Tastes great!

Delicious! Buffalo Producers celebrate National Bison Month in July as a great time to grill bison meat. Select any tender cut from Prime rib steak to hamburger! You might be amazed that it’s healthy as well as tasting great!

Producers want you to know that bison is the leanest protein available to consumers today, boasting 26% more iron than beef and 87% lower in fat. Bison has 766% more B12 vitamins than chicken, and 32% less fat, based on nutrient data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

6. Watch a Buffalo video

There are several good possibilities, both short and long videos, on the National Park Service (nps.gov), Public TV, and Wildlife Parks websites. Or you might decide to review some of our Blogs. We’ll have more suggestions for you after our Website goes live in November!

Fun Facts About Bison

1. Buffalo Survive just fine through long, cold Winters

Their hump is composed of muscle supported by long vertebrae, which allows them to use their heads to plow through deep snow and eat grasses below. They also thrive on cottonwood leaves and browse.

Fierce blizzards don’t faze them. Buffalo face into a storm rather than walking away from it. Or they lie down, letting it blow over. Thus they avoid being trapped by fences, water holes and creeks as happens to cattle and sheep—which travel with the wind.

2. Calves are born a Different Color than their Moms

Buffalo calves are called ‘red dogs’ by Forest Rangers. When born they are orange or cinnamon colored. It takes 3 to 4 months to grow a hump and spike horns, shed their baby hair and change to a darker color like their mothers. Their heads turn blackish first.

3. Buffalo can outrun most Mammals

Buffalo bulls may look big, slow and lazy. But don’t be fooled! They can spin on a dime, jump straight up and over a 5- or 6-foot fence, leap a 7-foot long jump, run up to 35 miles per hour and are strong swimmers.

In addition, it seems, a Buffalo bull on the fight can tear down most any fence that is in his way! So be sure to place something large—like a pickup truck—between you and that bull!

4. Moms are fiercely Protective of their Young Calves

Mothers stay close by their buffalo calves and fight off predators. However, if she has twins, a mother might select only one, walking away from the other. Does she perhaps realize she can care for only one lively calf? Or maybe she instinctively knows she won’t have enough milk to raise two healthy calves?

5. Dads and Uncles still Guard the Herd when they feel Threatened

When predators threaten, Buffalo bulls may circle the group into a tight herd, facing out and pawing dirt, with mothers and calves protected inside the circle.

6. Who really Saved the Buffalo from Extinction?

Those who really saved the Buffalo were ordinary people—westerners, ranchers, all buffalo hunters, with boots—or moccasins—on the ground. Separately, these families cared for and brought buffalo back in significant numbers for survival—onto the western plains and grasslands.

Without them American bison would likely have gone extinct! These 5 family groups saved calves one at a time. All had hunted buffalo, both Native American and white. They saw what was happening to the buffalo and cared about saving them.

Samuel Walking Coyote (or his son-in-law), and herd purchasers Charles Allard and Michel Pablo in western Montana

James McKay and neighbors in Manitoba, Canada

Pete Dupree and herd purchasers, the Scotty Philips in South Dakota

Charles and Molly Goodnight of Texas

Buffalo Jones of Kansas

At crisis time—in the 1880s and 1890s—these families were the only ones standing between live buffalo and determined hide and trophy hunters who poached even the few remaining Yellowstone Park herds down to fewer than 25!

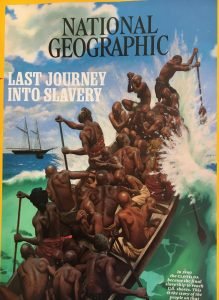

7. A President helped Save the Buffalo

The Buffalo Conservationists we know best are President Theodore Roosevelt, William Hornaday and George Bird Grinnell. Together they made a significant impact on wildlife conservation—particularly on buffalo.

Teddy Roosevelt, a frail child, built up his strength and endurance and helped restore buffalo after he traveled to Dakota Territory to hunt them in 1883. He shot an old bull and stayed to set up a cattle ranching enterprise. On his western ranch Roosevelt soon realized that the elk, bighorn sheep and buffalo that he so admired would not survive relentless overhunting. He grew increasingly convinced of the need to protect the buffalo and provide large, safe places for them and other wildlife to live.

As president—from 1901 to 1909—he became one of the most powerful voices in the history of American conservation and earned himself a place on Mt. Rushmore, SD, as this country’s greatest champion of public lands. Roosevelt created the United States Forest Service and established 150 national forests, 51 federal bird reserves, 4 national game preserves and set aside 230 million acres of public land. He worked with Congress to establish 5 national parks and dedicated 18 national monuments.

8. Native Americans are Interrelated culturally with Bison

The history of Native Americans and bison is culturally interrelated. Bison have been integral to tribal culture, providing Native people with food, clothing, fuel, tools, shelter and spiritual value from time immemorial.

Established in 1992, the InterTribal Buffalo Council works with the National Park Service to transfer excess Buffalo from national parks to tribal lands. It also gives assistance in management of herds and how to integrate traditional values to the experience.

9. Bison have poor Eyesight

Buffalo cannot focus well and are known to have poor eyesight. But with one eye on each side of their heads they are said to have good peripheral vision, able to keep track of 90% of the area that surrounds them. Handy for checking on lurking wolves!

Buffalo do have excellent senses of smell and hearing and communicate well with their herd. Cows and calves communicate using pig-like grunts and during mating season, bulls can be heard bellowing across long distances.

10. Bison have been around for Ages

These giants have such a special place in the country's history and ative American cultures and for good reason. They are fiercely protective yet calm animals that will do anything to protect their herds and their calves. They are truly North American treasures!

11. Buffalo are Social Creatures

They like living together in herds. But not just any group—their own herd. And not too large a herd—30 to 60 seems a good size. For most of the year, the buffalo sort themselves into “cow groups,” or maternal herds, and “bull groups.”

An older grandmother is the usual leader of the herd. She leads them to water at the time that seems right to her. Bull calves are allowed to stay in the herd with their mothers until they become too large and aggressive. Then they are kicked out of the maternal herd to join bachelor groups that wander at a short distance from the main herd.

In the wild herds of long ago, with roughly equal numbers of males and females, bachelor herds were known to be large.

Historically in late July and August, the great herds came together for rut, or breeding season. Today in managed herds, young bulls are usually sold off long before age three. They sell well in the market place for meat or as potential herd bulls. In Native tribal herds young bulls are especially desirable to provide meat for naming feasts and community gatherings. By giving of their meat, they honor the person celebrated, especially when the honored one is a young man.

This prevents buffalo herds from out-growing their pastures. Otherwise, the herd will double and redouble in a few years, soon over-grazing their pastures. Having fewer bulls also means less fighting, and makes breeding easier for the dominant bulls. The oldest bulls often range far from their home herd.

12. Buffalo Enjoy a Wallow

A little dust or mud won’t hurt. Called wallowing, bison roll in the dirt to get rid of biting insects and help shed their winter coat. Male bison also wallow during mating season to leave behind their scent and display dominance.

13. Watch Buffalo’s Tail for Warning

You can judge a Buffalo’s mood by its tail. When it hangs down and switches naturally, the buffalo is usually calm. If the tail is standing straight up, watch out! It may be ready to charge. No matter what a bison’s tail is doing, remember that they are unpredictable and can charge at any moment. Every year, there are regrettable accidents caused by people getting too close to these massive animals. It’s great to love the bison, but love them from the distance of at least 75 feet.

14. Buffalo eat Grass, Weeds, Browse

Pass the salad, please. Bison primarily eat grasses, weeds and leafy plants—typically foraging for 9-11 hours a day. That’s where the bison’s large protruding shoulder hump comes in handy during the winter. It allows them to swing their heads from side-to-side to clear snow -- especially for creating foraging patches. Learn how bison's feeding habits can help ensure diversity of prairie plant species after a fire.

15. Average Lifespan 10 to 20 Years

Bison can live up to 20 years old, but some live to be much older, especially with good care on ranches.

A buffalo cow may weigh 1,000 pounds, while the bull weighs twice as much, or up to 2,000 pounds! Cows begin breeding at the age of 2. For males, the prime breeding age is 6 to 10 years.

16. Improving Soil

Bison are known to play an important role in improving soil and creating beneficial habitat while holding significant economic value for private producers and rural communities.

17. Ancient Bison came from Asia

The American bison’s ancestors can be traced to southern Asia thousands of years ago. Bison made their way to America by crossing the ancient land bridge that connected Asia with North America during the Pliocene Epoch, some 400,000 years ago. These ancient animals were much larger than the iconic bison we know and love today.