Early American History

8th Grade Curriculum — North Dakota

Intro

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Dakota Origin Stories

Most of the people in North Dakota were nomadic or semi-nomadic until about 1100 A.D.

Archaeological evidence tells us that by then, some lived in permanent homes in fortified villages and became sedentary.

The people we know today as the Mandans moved into ND around the year 1000 A.D. By 1100, they had settled in several villages along the Missouri, Heart and Knife rivers. They were still living there in the 19th century.

They gathered in villages and built permanent houses and are known as sedentary tribes. Along their journey to this location, they learned about corn and how to grow it.

Other people continued to move around, usually following bison herds.

Because these people migrated to find game and plant foods, they lived in housing that could be easily packed up and taken with them, or they built shelters whenever they settled down for a littlewhile. They might have moved 12 to 20 times a year.

The buffalo were sacred and critically important to the Plains Indians because they provided food, clothing, shelter and many other necessary and religious items for them. Photo www.FirstPeople.us

This family poses for a photo next to their tipi home. The tipi is made of tanned bison hides. In the background, notice the meat drying. SHSND 0014-033.

We can learn a lot about the culture of the People and what qualities they thought were important by reading or listening to their origin stories.

Sweat Lodges were used as baths, or to purify the body, mind and spirit. A frame of willow, covered with bison hide, was set up over a fireplace. Red-hot rocks were put in the fireplace, and water was poured over them, making the lodge a hot, dark, steam room. Photo Christopher Davis.

The earliest People to come to ND had creation, or origin, stories. Some of these stories have been preserved through oral tradition. Oral tradition means telling stories about the creation to others, especially the children.

Most of the origin stories are very complicated and very long. There are many characters and many events. The stories are important today because they tell us about the spiritual beliefs and cultural traditions of the People.

Origin stories give us one view of how people came to live here. The stories were handed down from parents to children for centuries. We don’t know what people called themselves when they began telling these stories, but over hundreds of years, they came to call themselves Hidatsa, or Lakota, or Chippewa or another name.

Origin stories tell of some of the great struggles the people went through to emerge on the earth and become fully human.

They had to learn many things and organize into well-ordered communities. They had to learn to understand supernatural powers as well as the natural powers of the plants, animals, rocks and climate.

It is important to remember that some of these stories should be told only at a certain time of the year or under certain conditions.

Since we cannot always meet those conditions when we read the stories, we need to remember to be thankful that the stories have been recorded for us to read and be respectful of the spirit of the people who told these stories over the generations.

The Hidatsa

The new Four Bears Bridge is located at New Town, ND. It was completed and dedicated in 2005. Photo Neil Howe.

The Hidatsa have three different origin stories because they believe long ago, there were three different groups of people who eventually came together to become the Hidatsa.

The people established 13 villages along the Missouri that eventually became the 13 clans of the Hidatsa.

The Awatixa (ah wah TEE ha) believed that they were created on the shores of the Missouri River by the great hunter Charred Body, who brought the Awatixa (“People of the Village of the Scattered Lodges”) to Earth.

The Awaxawi (ah wah HAH wi) climbed to the surface of the earth by climbing up a vine.

These “People of the Village on the Hill” lived east of the Missouri River and raised crops until they migrated to the Missouri River and joined the Awatixa and Hidatsa-proper.

The Hidatsa-proper—“People of the Willows”—emerged from the earth near a large lake (often identified as Devils Lake).

The powwow is the oldest public festival in North America. Photo Gwyn Herman

the Hidatsa-proper learned how to grow corn from other people.

The Mandans

The Mandans were created in two events.

First Creator created the land, animals, plants, rivers and hills west and south of the Missouri River.

A spirit being called Lone Man created the flat land, ponds and grasslands east and north of the Missouri River. Lone Man also created cattle, sheep, birds and white People.

First Creator and Lone Man disagreed

Mandan Chief Four Bears. The Mandan Chief called Four Bears grew up along the Knife River near present-day Stanton, North Dakota. He received his name after a battle in which the other warriors said he fought like four bears. Photo SHSND C0597.

They probably traveled more during summer and fall when it was important to find game and plants to preserve for winter. Likely they moved less often in winter.

As the people made changes in their lives, they continued to remember their past and told the stories to their children. Every group of people has a story about where they came from and how they were created. The Bible and Koran tell of the Creation.

These stories came to be known as origin stories. They help us to reach back into the past to learn more about the earliest residents.

Many of the Dakota stories include buffalo because of their importance in the Native culture. Some groups have more than one original story.

They climbed up a vine and emerged through a hole onto the surface.

Tragically, a pregnant woman got stuck in the hole and prevented more people from climbing up the vine. The pregnant woman stopped the migration so there are still Hidatsa ancestors under the earth.

The Hidatsa-proper migrated around the Great Plains until they came to the Missouri River. Here they met the Mandans who helped them cross the river to the west bank.

The Mandans gave the name “Minitaree” or “Cross the Water” to the Hidatsas. Once they arrived at the Missouri River,

Tchung-kee was a popular sport with the Mandan and Hidatsa boys and men. These stones are on exhibit at the Knife River Villages National Historic Site. Photo ND Geological Survey.

about some details of creation, but eventually, Lone Man came to live among the Mandans.

The second event took place at the mouth of the Missouri River. There the people lived in a cave.

A young man left the cave and went to the surface. He returned to his people and told them about the land, so the Mandans left the cave, bringing corn and squash with them.

They lived in different places along the Mississippi River, but then returned to the Missouri River where they met the other Mandans.

Lone Man continued to live with the Mandans a long time, but then decided to return to his home, the south wind.

He promised the Mandans that he would return someday and in the meantime, they would always have his help.

Lone Man returns every spring as the warm wind.

The Arikaras

The Arikara origin story tells us that long

ago the people lived in Mother Earth.

Then, Mother Corn brought all the people out to the world.

At first, the people did not know how to live properly, so they wandered. As they

The Three Affiliated Tribes logo. Neil Howe.

wandered, some of them were made into fish, others into birds, moose, bears and other “animal people.”

Eventually, the Arikaras found a land (in modern Nebraska) that had everything they needed to live. Here, Mother Corn came to them and taught them how to live on earth and how to pray to Man Above.

Mother Corn died, but she left the corn plant to remind the Arikaras of her love for them.

The bullboat was made from the hide of a bison bull stretched over a willow frame. The round bullboat provided a way of transportation on the Missouri for the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara people. Photo Fort Abraham Lincoln Foundation.

Many years later, the Arikaras moved north to live along the Upper Missouri River.

The Dakotas

The Dakotas tell of coming from across the ocean where they had lived in the land of cold winter and much ice.

They crossed the ocean in boats. When they landed, they found a place where there was plenty of game and other things they needed.

They migrated westward and met the Chippewas in a place where there were three large lakes. While they lived there, white people came, bringing metal tools.

These tools caused trouble for the Dakotas with the Chippewas, but the Dakotas drove the Chippewas away.

The Dakotas continued to move west until they reached the Mississippi River Valley where they settled in permanent villages.

The Lakotas

The Lakotas believe that long ago, there were only four people on earth.

One of them was the Trickster, Iktomi. Iktomi tricked Anog-Ite into telling him how to get other people from under the earth.

The people under the earth were six men and their wives and a young man named Tokahe, The First One.

Iktomi invited them to the surface. He told them that the world was full of food, clothing and everything they needed. But Iktomi had tricked them; the people found nothing that they needed.

Anog-Ite’s parents, Waziya and Wakanka helped the people by bringing them food and water. Waziya and Wakanka led the people to the forest and showed them how to hunt and live on the earth.

As many as 30 million bison probably roamed the grasslands, prairies and plains of North America. After Native Americans obtained horses in the mid-1700s and could trade for guns, hunting became easier for them. Sketch SHSND 970.1 C289NL

The people learned well how to live and had children. The children of these people are the Lakotas (Sioux).

The Chippewas

Standing Rock Monument is located near the entrance to the Standing Rock Tribal headquarters in Fort Yates, North Dakota. Neil Howe.

Sketch of a Métis campsite. Notice the Red River carts next to each tipi. SHSND C0621.

The earth, the sun and the moon were created by the Great Creator, Kitchie Manitou.

Kitchie Manitou also created the plants, rocks, trees, animals, wind and birds. He sent the birds in the four directions (north, south, east and west) to carry life to every place.

Then, when all of the plants and animals had been created, Kitchie Manitou took four parts of Mother Earth and blew into them creating Man.

Kitchie Manitou then lowered Man, the last creation, to the earth. Man considered all of creation his elders because they came before him.

The Chippewa people who descended from Man first lived by a great salt water, a long way east of where they live now in Wisconsin, Minnesota and North Dakota.

For many years, the Chippewas migrated west, always trying to live closer to the place where their Me-da-we religion could be practiced in its purest form. They finally reached the proper place which was La Pointe Island in Lake Superior (the Apostle Islands).

From here, the Chippewas spread in many directions. Some of them migrated into North Dakota, where they lived and hunted between the Red River and the Turtle Mountains.

For the earlier 8th grade ND Studies see the following: https://www.ndstudies.gov/gr8/content/unit-i-paleocene

Plains Villages—Corn Culture

Birds-eye view of a Mandan village. Painting, Photo credit SHSND 970.1C289NL

Though the Mandans, Hidatsas and Arikaras grew enormous quantities of corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers, their agricultural practices were very different from the ones farmers use today.

On-A-Slant village was built about 400 years ago near what is now Mandan, where the Heart River runs into the Missouri River.

In 1915, a Hidatsa woman named Maxidiwiac (Mah HEE dee WEE ah), described to the anthropologist Gilbert Wilson her methods of growing corn.

She used traditional methods learned from her mother and generations of women before her.

Maxidiwiac was known as Waheenee (Buffalo Bird Woman) when she was a young girl. At the age of 12, she began to assist her mothers in the garden. (Hidatsa children call their birth mother and her sisters “Mother.”)

Her first job was to sit on the watchers’ stage, a platform where little girls spent the day chasing crows and little boys away from the corn.

When she grew to be a mature woman, Maxidiwiac had her own garden. She was responsible for planting, protecting, hoeing and harvesting.

Her tools were made of iron and wood, but some women still used the traditional tools made of wood handles attached to antlers for rakes or wood handles attached to bison scapulas for hoes. The ground was prepared for seeding by digging with a sharply pointed stick.

Tools were made and used by Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara women for centuries, but when European American traders began to trade with these tribes, they brought hoes and rakes made with iron.

Many women kept the old tools because they could make them from local materials and did not have to depend on traders for their tools.

This display of original gardening tools used by the women of the three tribes shows, from top down, a digging stick, a wooden rake, a hoe made with the scapula (shoulder blade) of a bison, and a rake made with a deer’s antler. In the middle is a braid of dried corn. Photo credit SHSND 0075-0386.

As an older woman, Maxidiwiac in her garden demonstrates corn drying and storage.

Horses made everything easier, from hunting buffalo to moving camp and hauling garden produce for storage from the Missouri River lowlands up the hill to Mandan and Hidatsa earthlodge.

Horses were also important in arranging a marriage between young people. The Mandans had several systems for arranging a marriage. In one form of marriage, a young man’s family found a young woman who would make a suitable wife for their son.

The man’s parents offered horses to the parents of the young woman. If the woman’s parents agreed that the young man would make a good husband for their daughter, they accepted the horses.

Maxidiwiac’s garden plan shows rows of corn (c) alternating with rows of beans (b). Between the corn/bean patches are rows of squash (sq). Sunflowers (sf) were planted around the edges. The corn was planted about 12 feet from the garden fence so that stray horses could not reach the corn by leaning over the fence.

Gardeners tried to avoid cross-pollination of their corn plants so they could maintain the genetic purity of the corn varieties. This illustration shows that one woman would plant the same variety of corn (A) next to her neighbor’s corn (A’). B and B’ were another variety of corn. Through cooperation and planning each woman could protect her seed corn for the following year.

First, Maxidiwiac, Buffalo Bird Woman, stirred up the dirt of last year’s corn hill with her hoe. She smoothed the soil with her fingers and placed six to eight dried corn kernels from the previous year’s crop in each hole. She patted dirt over the seeds with her fingers and moved on to the next hill which was about four feet away.

Each morning, Maxidiwiac planted several rows, each 90 feet long. Other women may have planted more or less corn according to the size of their families.

If a woman was ill and could not plant, members of her social group would plant for her. If they worked together, they could complete the planting in one morning.

Maxidiwiac’s garden was about three and a-half acres in size. It was divided into sections in order to keep different varieties of corn from cross-pollinating one another.

As the corn grew, the women hoed daily to keep the weeds from taking over the garden. They made scarecrows from wood frames and old blankets to keep the crows from stealing the young corn.

In early August, Maxidiwiac looked for signs that her corn was ripe.

“The blossoms on the top of the stalk were turned brown, the silk on the end of the ear was dry, and the husks on the ear were of a dark green color.”

This was “green corn” which was boiled and eaten fresh. Green corn was considered a great treat. Later in the summer, other varieties of corn were harvested and dried on the cob or as kernels. The dried corn was saved for the family’s winter use and for trade.

Seed corn was specially selected and set aside. Maxidiwiac “chose only good, full, plump ears” without any sign of disease.

She put away enough seed corn to last for two years, so that if the crop failed in the next year, she still had seed for the following year.

Maxidiwiac raised nine varieties of corn. Each type had a different use: some were better for eating fresh, others better for drying. Some corn was ground to make flour.

To maintain the purity of their corn genetics, the women kept each variety separate.

Maxidiwiac usually coordinated her planting with the woman who had the neighboring garden so that their gardens would not cross-pollinate.

In this Hidatsa woman’s garden, beans were planted between rows of corn. Each variety of corn was planted in a patch that was separated from other varieties. Squash was planted between corn patches. A typical garden was about 3 to 5 acres in size. SHSND 0086-0307.

Corn was an important food for the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara and it also had spiritual quality. The people of the villages performed certain ceremonies to ensure that they would always have a good crop of corn.

Corn agriculture gave the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara a secure and reliable source of nutrition. In addition, the tribes were able to trade their surplus corn for other goods and in that way, they became wealthy.

Mothers taught their daughters how to raise corn and other crops. Women of the tribes accumulated information on methods of raising corn and maintaining the qualities of each variety.

It was women’s work, agricultural skills and knowledge that brought economic and social advantages to the tribes.

These women were braiding corn for drying. Buffalo Bird Woman usually made 100 braids of dried corn for winter storage. The braids could be hung in the earthlodge. SHSND 0086-0277.

Yellow Nose sits with her husband Bear on the Water in front of their Mandan home. She uses a mortar to pound dried corn into flour. Behind them is a pile of braided dried corn. SHSND A0126.

Mandan and Hidatsa Horses

The Mandan and Hidatsa acquired horses at about the same time as the Lakotas did, around the middle of the 1700s.

Like the Lakota, Mandan and Hidatsa made a place for horses in their culture. They found that horses were very helpful in hunting bison and allowed them to travel much farther in search of the wild herds. Work became easier.

Horses did not change traditional village organization, but the acquisition of horses became an important “calendar” date. Events were identified as having happened before or after the tribes acquired horses.

An Earthlodge. Mandan and Hidatsa lived in roomy, comfortable earthlodges. To protect their horses from raids, the men often brought their best hunting or war horses into the lodge. Women brought corn husks and stalks to feed them. The plan of this typical earthlodge, shows the small corral on the right side for horses, near the lodge door. SHSND.

Horses were so important that they soon became integrated into many village traditions. Both men and women owned horses. However, women owned mares and foals while men owned stallions and geldings. Women had horses for riding and horses for carrying burdens.

Mandan men acquired horses through raiding the herds of their enemies, but women acquired horses through certain family or clan relationships.

A young man paid respect to a woman of his family or clan by offering her horses. When a young man went on his first horse raiding expedition, he gave the horses he captured to his eldest sister. This was a way of honoring her.

If his sister was already married, she extended that honor by offering the new horse to her husband. If a young man struck his enemy while capturing horses, he would be given a new name by an elderly woman of his father’s clan. The young man paid the woman for this honor by giving her horses.

The bride’s parents then gave the horses to their sons, who honored their sister (the bride) by giving the horses to her. The bride offered the horses to the father of the young man she was going to marry. In this exchange, both families acknowledged their approval of the marriage and showed respect to each family.

Mandans and Hidatsas considered horses to be a sign of wealth. The trading of horses between the families symbolized to the bride’s family that the young man came from a respectable family with enough resources to provide well for the young woman and her future children.

The young man’s family offered enough horses (wealth) to demonstrate to the bride’s family that they held the young woman in high esteem.

Horses did not come to the Mandans and Hidatsas without some notable problems. Horses like to eat young plants and corn at any stage of growth, so they had to be kept out of the large gardens where the women of both tribes raised corn, squash, beans and sunflowers.

Women usually erected platforms in the garden where they or their children watched over the growing crops and kept horses and other garden-raiding animals away. The platforms were also used for drying corn and squash and other plants after harvest.

Horses also needed feed in the winter, especially when the snow was too deep for them to reach the grass. Usually cottonwood or willow bark served as winter feed, but finding and carrying winter feed to the horses added extra labor to ordinary winter chores.

Buffalo Bird Woman and other Hidatsa and Mandan women fed corn stalks to their horses, but also had to prevent horses from destroying the gardens.

Maxidiwiac (1839-1932) explained gardening to Gilbert Wilson around 1915, when she was a very old woman. In the following paragraphs, taken from Gilbert Wilson’s ‘Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden,’ Maxidiwiac describes how Hidatsa gardeners adapted their gardening methods to horses.

Acquiring Horses, by Buffalo Bird Woman

“At the very first it is true, we did not own ponies; but we soon got them. I think my tribe obtained ponies from the western tribes. In my own youth we Hidatsas got many of our horses from western tribes, especially from the Crows.

“In the early part of the harvest season, when we plucked green corn to boil, we gathered the ears first.

“Afterwards we gathered the green stalks from which the ears had been stripped. These stalks with the leaves on them we fed to our horses, either outside the lodge, or inside, in the corral.

“We commonly husked our corn, as I have said, out in the fields, piling up the husks in a heap. After the corn was all in, we drove our horses to the field to eat both the standing fodder and the husks that lay heaped near the husking place.

“Horses readily ate corn fodder and by the time spring came again, there was little left in the field. Not only were the husks devoured, but most of the standing stalks were eaten off nearly or quite to the ground.

“Okĕi’jpita. . . is a small ear that sometimes appears at the top, on the tassel of the plant. Okĕi’jpita ears, if large enough, we gathered and put in with the rest of the harvest. But smaller ears of this kind, hardly worth threshing, we gathered and fed to our horses.

“Sometimes, if the harvesters were in haste, these ears were left in the field on the stalk; a pony was then led into the field to crop the ears.”

Protecting the Gardens from Horses

“Horses did not trouble us much, as we did not permit them to graze near our garden lands. They were pastured on the prairie,” said Maxidiwiac.

“We always had fences around our fields as long ago as I know anything about and I have heard that our tribe had such fences in the villages they built at the mouth of the Knife River, to protect their fields there from their horses.

“Such, I have heard, has been our Indian custom since the world began.

Bridle band. This brow band fit across the horse’s face above the eyes. It symbolized how much the owner treasured his or her horse. The brow band is made of leather decorated with dyed porcupine quills, tinkling cones and dyed feathers. This band is in the collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota. SHSND Museum, Hoffman Collection.

“I think our fences stood 12 or 15 feet away from the cultivated ground, as I pace it here on the ground. I know no reason why they were run thus, except as I have said, to keep the horses from nibbling the corn.

“You see, 15 feet is quite a little distance and the fence could have stood closer to the cultivated ground and still been far enough away to keep the horses from nibbling the crops. All I know is that it was a custom of my tribe and I always followed this custom if I had a fence to build.

“Pacing it off here, on the ground, the length of the stage was, I think, about so long–30 feet. Its width was about thus–12 feet.”

Stage platforms were built for watchers to protect the gardens from horses, birds and boys as crops began to ripen. This sketch shows ladder at left, buffalo calf skin folded fur out made seat for watcher, folded to make a cushion for sitting on the uneven pole floor. A tree may be incorporated for more shade. Sketch from Bird Woman’s Book.

Three poles supported a second calf skin used as a shield against the sun. Three moveable poles could be shifted to provide shade through the day.

“From the ground to the top of the stage floor was a little higher than a woman can reach with her hand, or about 6 feet, 6 inches. There were horses in the village and the stage floor must be high enough so that horses could not reach the corn.

The woman above is placing slices of squash she has threaded onto long sticks for drying. Corn and other foods as well were laid on the platforms to dry and preserve for winter eating.

“The season for watching the fields began early in August when green corn began to come in; for this was the time when the ripening ears were apt to be stolen by horses, or birds, or boys.”

Dried foods were then placed in cache pits for storage within and just outside the earthlodges which were built on plateaus higher up above the river.

Maxidiwiac explained that she dug the cache pit like a jug—deep enough so she could just see out the top and as large as a bullboat at the bottom. Then she lined it with grass and filled it with dry corn and vegetables.

“The pit was dug into the ground in the shape of a jug. The entrance was about 2 feet across and the size of a bullboat at the bottom. It took two or three days to dig.”

The big ones had a ladder, the smaller ones when standing on the floor, her eyes just cleared

the top of the ground above. The cache pit was lined with a special bluish grass that did not mold.

They covered the cache and heaped earth in the pit until it was level with the ground.

“Lastly, we raked ashes and refuse dirt over the spot, to hide it from any enemy that might come prowling around in the winter, when the village was deserted.”

Smaller caches may be buried inside the lodge itself. “A cache pit lasted for a long time, used year after year,” she said.

Horses for Carrying Burdens

“In the fall, when we went to our winter lodges, corn, squash, beans and whatever else was needed, we loaded on our horses and took with us. As soon as we came to our winter lodge we made ready a cache pit at once and stored these things away.

“We Hidatsas did not like to have the dung of animals in our fields. The horses we turned into our gardens in the fall dropped dung and where they did so, we found little worms and insects.

“We also noted that where dung fell, many kinds of weeds grew up the next year. We did not like this, and carefully cleaned off the dried dung, picking it up by hand and throwing it 10 feet or more beyond the edge of the garden plot.

“We did likewise with the droppings of white men’s cattle, after they were brought to us.

“I do not know that the worms in the manure did any harm to our gardens, but because we thought it bred worms and weeds, we did not like to have any dung on our garden lands and we therefore removed it.”

Horses brought significant changes to the Mandans and Hidatsas, but having them did not change the fundamental organization of the two tribes.

Although horses also gave them greater mobility, the two tribes continued to live in permanent villages. The Mandans and Hidatsas, like the Arikaras who joined them later, incorporated horses into their long-standing traditions.

Gilbert Wilson wrote Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden after long conversations with Maxidiwiac about the gardens of Hidatsa women. Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden: As Recounted by Maxi’diwiac (Buffalo Bird Woman—Waheenee 1839-1932) of the Hidatsa Indian Tribe. Originally published as Agriculture of the Hidatsa Indians: An Indian Interpretation. Edited by Gilbert L Wilson, 1868-1930. http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/buffalo/garden/garden.html#XI

Horses Return to Native Americans

Horses evolved in North America. They went through many stages, evolving from three-toed to one-toed and increasing in size to about the size of a deer.

They were well-adapted to the grasslands of North America, but they disappeared from the continent around 10,000 years ago. Scientists do not know why horses disappeared. It may have been because of some ecological disaster, disease, over-hunting by humans or all three.

Paleontologists have discovered that some North American horses migrated westward and crossed the Bering Land Bridge into Asia where they prospered. Whatever the cause, there were no horses (Equus species) in North America from about 10,000 years ago until about 1520 A.D.

When Columbus made his second expedition to the Caribbean islands, he brought horses, but it is doubtful that any of those animals were released on the continent.

In 1519, however, the Spanish explorer Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) brought horses into the southern Great Plains of the continental mainland. Horses had returned to North America, but they were now domesticated animals trained to work for humans.

Spanish explorers, missionaries and rancheros kept horses for transportation, for beasts of burden and for farm work.

However, they closely guarded their horses and did not let American Indians own them.

This intricately braided rope, or horse rein, was made from red (sorrel), black and white horse hair. It was probably used only for ceremonial purposes. This rope is in the collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota. SHSND Museum 10934.

Many tribal historians believe that American Indians only rarely captured and trained wild horses.

American Indians acquired horses in 1680, when Pueblo peoples, led by Popé, drove the Spanish from New Mexico and captured the horses left behind. Comanches, Utes and Apaches captured horses and developed the skills they needed to ride and hunt on horseback.

Trade between tribes brought horses north from New Mexico. The Shoshonis (who now live in Montana) often made

journeys south to trade for horses.

Their trade involved more than horses. They also traded buffalo robes and other goods for bridles and saddles. Using the Spanish model, American Indians made their own bridles and saddles.

By 1700, a few horses had reached the tribes of the Upper Missouri River country. By 1750, horses had become incorporated into the life ways of Indian tribes and were part of a web of trading and raiding among the tribes.

Horses brought great advantages to Indian tribes. Hunters could travel farther to find bison herds. Horses added speed and efficiency to the bison hunt. They carried heavier and larger burdens than a dog or human could carry.

However, horses also brought disadvantages. Horses competed with bison for grass and water. Horses could go only where there was enough grass and water for the herd, which limited the destinations of the nomadic tribes.

They required grass or cottonwood tree bark for winter feed. Riders were occasionally injured by a fall from a horse.

Like metal goods and guns, horses arrived on the northern Great Plains in advance of non-Indian traders and explorers.

Though horses and other European trade goods brought many advantages, they were also a sign that white soldiers and settlers would soon follow.

Lakota Horses

During the decades before 1650, Lakotas, a branch of the large Dakota (sometimes called Sioux) nation, lived in the woodlands east of the Red River.

During the 17th century, they moved into the Great Plains and occupied the land between the Red River of the North and the Missouri River.

They began to live a more nomadic life than they had in the woodlands. They followed bison herds and became expert hunters.

Man’s saddle—side view. The saddle is made of two pieces of wood joined by a piece of elk horn in front (pommel) and in back (cantle). This style of saddle would have been used by a man. After 1800, the owner of the saddle might have added metal rings or other pieces he acquired in trade. State Historical Society of ND collections. SHSND Museum 1982.285.38.

Horses became an important part of Lakota society because Lakotas were nomadic. Lakotas moved their villages to places where they had good grass and water for their horses and nearby bison herds.

Horses made moving the village much easier because they could carry a heavy load. Horses

also made bison hunting more efficient because a horse could carry a hunter very close to the bison herd.

Before the Lakotas and other tribes acquired horses, they used dogs to carry burdens. The dog travois was similar to the horse travois, but much smaller and it carried much lighter loads than a horse travois. Making and packing the travois was women’s work among the Lakota. SHSND 1952-6303-2.

This horse has a traditional saddle and halter. Saddle of wood, is joined with elk horn in the front (pommel) and back (cantle). The halter is made of rope or twisted rawhide, but it is fashioned in the traditional manner without a metal bit. The horse pulls a travois of tipi poles. A baby is carefully secured to the webbed “basket” between the poles. The horse’s foal stands behind her. SHSND 0739-v1-p52.

A Lakota family might own several horses, but a bison hunting horse was a special animal that was not used for other purposes, except perhaps war. When a man wanted a hunting horse, he selected a fast young horse and trained it to hunt bison.

He would ride the horse alongside and into herds of running horses. In this way, the horse became trained for speed and learned how to approach a moving herd of animals. The hunter also rubbed bison robes over the horse so it would learn to know and not fear the smell of bison.

Rope. Horses brought many advantages to American Indians. Though Indians had made rope from the wooly hair of bison for centuries, rope-makers strengthened ropes by adding horse hair to the braided fibers. This braided rope is made of horse hair with a little wooly hair included. State Historical Society of ND collections. SHSND Museum 583.

Older men and boys sometimes used saddles in the bison hunt. The saddle was made from two pieces of wood, about 20 inches long and one and one-half inches thick. The two pieces were joined by an elk antler that was shaped and fitted to form an arch just behind the horse’s withers.

Another piece of elk antler joined the two pieces of wood behind the rider.

Raw bison hide covered the entire saddle and was stitched into place with sinew. When the rawhide dried, the wood and antler saddle was very strong. The saddle was attached to the horse with a girth of bison leather.

Some hunters made stirrups of buffalo hide or

According to the winter count of Battiste Good, the southern bands of Lakotas first saw horses around 1700. By 1715, horses appeared frequently in Good’s winter count.

Sometime in the middle 18th century (around 1750), Lakotas used horses regularly for hunting and transportation. Most likely they traded with other tribes for horses as they found out how useful horses could be.

Man’s saddle---front view. The entire saddle made of wood and elk horn was covered in “green,” un-tanned bison hide that was stitched with sinew and allowed to dry. This saddle was very strong and might have been used for generations. State Historical Society of ND collections, SHSND Museum 1982.285.38.

This woman’s saddle is similar to a man’s saddle, but the elk horn pieces in the front and the back rise higher than a man’s saddle. The higher pommel and cantle allowed a woman to carry bags of goods and even small children (safely secured to the saddle). State Historical Society of ND collections, SHSND Museum 1991.41.2

These stirrups of the traditional Indian saddle were made of wood covered with hide. Some stirrups were made from rawhide without wood. These stirrups were used with the saddle. State Historical Society of ND collections, SHSND Museum 1982.285.38

Bison were central to Lakota culture, but the Lakota also loved and honored their horses. Decorative painting on tipis and hides often depicted Lakota men on horseback. On this tipi, the lowest row of horses and riders appear to be racing. The upper images seem to indicate scenes of warfare. SHSND 1952-5531

Horse owners often decorated halters to demonstrate the high value of their horses. This bridle brow piece was decorated with dyed porcupine quills, metal tinkling cones, and tassels. State Historical Society of ND collections. SHSND Museum 1882.

Some hunters rode after the bison herd with only a halter on their horse. Others used a saddle as well.

When a Lakota horse was prepared for a bison hunt, it had a halter, or head piece, that was made of leather tanned from a bison hide. There were two leather straps: one strap encircled the horse’s muzzle just behind the corners of the mouth.

This strap was attached to another strap that passed behind the horse’s ears. Another long leather strap was attached to the halter and extended back to the rider. The halter fit somewhat tighter than modern halters.

Horses were highly valued by their owners. Owners often “dressed” their horses in beautifully decorated bridles and saddle bags. This saddle bag was to be carried across the horse’s back behind the saddle. Though there is a small opening in the saddle bag, this one was not designed for practical use. Evidence indicates that this saddle bag may have been owned by the great Lakota leader Sitting Bull. State Historical Society of ND collections. SHSND Museum 11711.

wood. These well-made saddles might have been used by generations of Lakota hunters.

Some Lakota horses were used to pull loads packed onto a travois (TRAV-wah, or TRAV-voy). A travois was made using tipi poles which were inserted into a harness placed over the horse’s back.

A webbed basket was suspended between the poles for carrying children, elders, or ill adults, household goods, or bison meat. Before horses came to the northern Great Plains, dogs pulled much smaller travois.

A woman who could pack a travois efficiently and well was held in high esteem.

Horse hair had many uses, too. It could be removed from the mane or tail without hurting the horse and might be used to decorate a headpiece or clothing.

Horse hair was also added to bison hair in making very strong ropes. Lakota artists often used images of horses in painting or beadwork.

Lakotas loved and cherished their horses. For special occasions (religious ceremonies or war) a horse might be painted with symbols that were important to its owner.

Some people decorated their horse’s bridles, saddles and saddle bags with beads or quillwork.

One mask (in the Smithsonian Institution today) was made of bison hide. Holes were cut in the hide for the horse’s eyes and ears. The hide was decorated with feathers.

Horses came to represent wealth to the Lakotas. Both men and women could own horses.

Men might acquire horses through trade or in raids. A woman might receive a horse as payment for her beadwork.

But, in the Lakota tradition, wealth was to be given away to honor someone else who had done a great deed, or to honor someone who had died. Horses often changed hands in giveaway ceremonies.

Historians debate the impact of horses on the Lakota way of life. Some historians argue that horses changed the Lakota way of life and even had an impact on their religious ideas. Other historians state that horses allowed Lakotas to improve, but not change, their way of life.

The Lakota economy—or way of making a living—did not change greatly when they acquired horses. Lakotas continued to hunt bison and incorporate the great animal into every aspect of their lives.

Because horses made bison hunting so much more efficient, they, too, came to be honored in many parts of Lakota life.

Once the bison were gone from the northern Great Plains, some horses remained with the tribe to connect the Lakota people to their pre-reservation past.

Hunting Bison

Wolf Chiefs’ story of Hunt

All the tribes used bison hides, hooves, heads, horns, tails, bones and many internal organs to furnish the necessities for a comfortable life. Skulls and other parts were important culturally for religious ceremonies. Photo by James Kambeitz, Bismarck State College Bison Symposium.

Bison supplied immense quantities of meat for the tribes that hunted on the Great Plains.

Some of these tribes, including the Lakotas, Dakotas, Yanktonais, Chippewas, Mandans, Hidatsas and Arikaras, lived on the Great Plains.

Other tribes lived to the east in the woodlands of Minnesota or west in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains and traveled into the Plains every summer to hunt bison.

So important was this animal to the well-being of American Indian tribes that they organized themselves every summer to travel as far as necessary to find bison, kill sufficient numbers for winter food supply and carry the meat back home again.

These hunts required careful and exact organization. The tribe’s well-being depended entirely on a successful hunt.

Some people have called bison the “grocery store” of American Indians. Perhaps “shopping mall” would be even more appropriate, because nearly everything the people needed and used was available from the bison carcass. Image by Cassie Theurer.

Bison was the raw material from which American Indians of the Great Plains made their living.

Bison provided meat, bones to be made into tools, hides for clothing, housing, bedding and containers.

Hunting required great skill and courage, but it also took skill to tan the hides, shape the tools and preserve the meat.

Both nomadic tribes such as the Lakotas and the sedentary tribes such as the Mandans hunted bison. All tribal peoples also hunted deer, antelope and elk. They also fished and trapped birds, but no other animal provided the food security that bison did.

In addition, all the tribes used bison hides, hooves, heads, horns, tails, bones and many internal organs to make the necessities for a comfortable life.

Parts of the bison were used to make toys for children, such as ribs for sledding.

Gilbert Wilson asked Goodbird and Wolf Chief to draw pictures of the stories they told.

These two

images show how they

made a sled from

bison ribs joined by rawhide thongs. One or two children could sit on the sled and slide down a snowy hill. From Gilbert Wilson Reports 1914, Sketches. Courtesy Minnesota Historical Society and American Museum of Natural History.

During most of the year, any family or village that needed meat could go out to hunt bison, deer, elk or antelope.

However, the big summer and early fall hunts were conducted for the entire tribe. The summer hunt was organized by tribal leaders whose decision had to be obeyed by all members of the tribe.

Anyone who approached the bison herd without permission would be severely punished. Usually, one of the young men’s societies was given the authority to maintain order among the tribe so no one scared off the bison herd.

Hunts were often preceded by religious ceremonies such as the Sun Dance. During these ceremonies, the people made spiritual sacrifices to ensure a successful hunt.

For many of the tribes of the northern Great Plains, bison held a special spiritual significance.

The summer hunt was a good time for children to learn the important tasks of an adult. Girls learned to prepare food, mend clothing and pack for hunting camp. Boys learned to hunt and to obey the hunt leaders.

Many rules, skills and ceremonies were passed down from parent to child during the summer communal bison hunt.

My First Buffalo Hunt, by Wolf Chief

Wolf Chief was born into a Hidatsa family around 1850. As a young boy, he accompanied his father and other hunters on the summer hunt, though it was not yet time for him to participate in the hunt.

This was his first lesson in the work of adult men of his tribe.

More than 60 years later, Wolf Chief told the story of his first hunt to Gilbert Wilson, an anthropologist who recorded many stories of the old ways of the Hidatsa. The story has been edited slightly.

When I was about 12 years of age, all the people of our village went on the west side of the Missouri] River toward what is now the town of Dickinson, for we had heard that buffalo herds were there. We crossed the river in bull boats . . . .

My father, Son of a Star, was chosen leader of the hunt and Belly-up was his crier. We made our first camp just outside the timber of the Missouri.

The next morning our people struck tents . . . . The young men went along the side of the road on horseback. In old times when we made a march like this, a large number of the people walked . . . .

The season of our march was in the first part of July. Before we left Like-a-Fish-Hook village, all the families hoed their gardens free of weeds so that we could leave them in safety, knowing that our crops would be in good condition when we returned.

We made six or seven camps before we found any buffaloes. As we came near to Cannonball River, my father sent two young men ahead to see if they could find any buffaloes. They returned saying, “There is a big bunch of buffaloes over there.”

They made their report on returning that evening. Everybody got ready for the hunt the next morning.

We arose early in the morning and my father saddled two horses while I also saddled one, for I was going with the hunting party.

I had a white man’s saddle, small for a boy, which I had gotten from the Crow Indians. Both my father’s horses had elk horn saddles.

In the rear of his saddle he tied short ropes in a twist, like a figure eight. This was to be used to bind the meat on the saddle when we came home from the hunt.

The party was made up of about 40 men, each leading an extra horse and 8 boys of from 12 to 15 years of age, each riding a single horse only, not leading one. A boy of 16 or 17 was thought old enough to be a hunter.

The 40 men were young men, or men in their prime, that is, of hunting age.

With us boys, who did not expect to take part in the actual hunt, went 3 old men, one of them carrying a bow and arrows. I do not think he really expected to use them but carried them more for the sake of old-time customs.

The 3 old men and we smaller boys, were not expected to take part in the actual chase of the buffaloes.

The leader of the hunt had been appointed the night before. He was Belly-up, or E-da´-ka-tas. Our name for a leader of the hunt was Matse´-aku´-ee, or, keeper of the men.

The name for my father’s office, leader of the tribe on the march, we called Madi-aku´-ee or tribe-traveling keeper.

Belly-up went on ahead and all the rest of us followed. We went out about five miles. Then we sent out two men on ahead . . . to spy out the herds.

We went at a smart trot. Pretty soon we saw our two scouts returning. They reported to Belly-up that they had located the herds.

The herd went tearing off. Only a fast horse could overtake buffaloes and indeed, a fleeing buffalo could outrun many speedy horses. “We killed only cows. The flesh of the bulls was tough,” reported Wolf Chief. Photo JK, BSC Bison Symposium.

They returned at a gallop, so we knew before they had reported, that they had news to tell. Belly-up now pressed forward faster and we all followed at a gallop.

All the men had quirts, as had Belly-up himself and I remember how the quirts would come down, “Slap, slap,” on the horses’ flanks and the hoofs go “Beat, beat” on the stones.

About a half mile from the buffaloes we stopped on the hither side of a hill which hid the buffaloes from view. The men took the saddles off the horses they were riding and put bridles in their mouths made of raw hide ropes, then remounted.

Belly-up went off a little way, took out a piece of red calico, tore off a strip and tore it into three or four pieces. These pieces he put on the ground as he faced in the direction of the buffaloes.

He spoke something, evidently a prayer. I could not tell what he said, but I knew that the red cloth was a sacrifice to the buffaloes.

Everybody now got ready and the men mounted their horses and stood in a long line facing the buffaloes, with Belly-up on the extreme right.

Of course, I mean only the hunters. The line now started forward at a sharp gallop, with all the heads and necks of the horses even, in a long line.

A soldier Indian, a man named Tsa-was, rode in front, and if any man got too far forward in the line, Tsa-was, or “Bears Chief,” would strike the horse in the face.

We boys had to follow behind with the 3 old men. These were old men of about 60, or more. One of them, as I have said, had his bow and arrows along, but all the young men in the hunters’ line had rifles. We were all on the leeward side of the buffaloes.

As we came over the brow of the hill we sighted them about four hundred yards away. Belly-up gave the signal, “Ku kats! Now’s the time!”

Down came all the quirts on the flanks of the horses, making the ponies leap forward like big cats. Everyone now wanted to be first to get to the herd and kill the fattest buffalo.

I was somewhat scared, for the horses were at break-neck speed and my pony took the bit in his mouth and went over the rough, stony ground at a speed that I feared would break his neck and mine too.

“Bang!” went a rifle. A fat cow tumbled over.

“Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang!” The herd swerved around and started up wind as buffaloes almost invariably did when they were alarmed.

The herd went tearing off. Only a fast horse could overtake buffaloes and indeed, a fleeing buffalo could outrun many speedy horses.

We killed only cows. The flesh of the bulls was tough and that of calves, when it was dried, became soft and was easily broken into pieces. For this reason, we did not often kill calves, although we sometimes did for the skins.

My father had killed three fat cows in the hunt, for he was along with the party. He butchered the cows and brought his spare horse (which he had left behind the hill, hobbled) and loaded it with meat.

He put a little of the meat also on the horse that he rode, but none on the pony I rode.

As he was cutting up the carcass, I saw him throw away what I thought was a good piece of meat.

I hated to see that piece of meat wasted and when I thought he was not looking, I picked it up and threw it back on the pile.

When we got home, I overheard my father say to my mother, “Our boy is not a wasteful boy—he wants to save what he has. He threw back on the pile of meat, some tough leg meat that I had thrown away. He did not want to see it wasted.”

He returned back to the camp from the place of the hunt much more slowly than we had gone thither. Sometimes we went at a trot, very often at a walk.

Almost every part of the buffalo was used in the old times. The choice cuts, with the shoulders and hams, we carried home, but the spines, neck, and heavier pieces we left behind on the prairie, covered over with hides.

The next day we came back to the place of the hunt for the meat we had left behind. We found it safe and carted it back to camp.

We spent two days drying the meat and making bone-grease. We did not dry the meat in smoke but on stages in the open air.

The tribes used different techniques in hunting. Some drove bison herds over a cliff or into a small canyon. Others surrounded the herd and then approached for the killing.

As soon as the bison were killed, women removed the hides and began to cut the meat into pieces. Usually some of the meat was consumed immediately as the tribe or band celebrated a successful hunt, but hundreds of thousands of pounds of meat were dried for winter use.

Women sliced the meat into thin strips and hung it on poles in the sun near a small fire to dry. Dried meat did not spoil.

Many of the tribes dried the meat at the hunting camp before returning to their villages. While the meat was drying, the hides were stretched out on the ground and staked down.

Women then scraped the hides clean of all flesh and began the process of preserving the hide. Hides might be tanned for robes. Other hides might be left untanned and used as rawhide.

Hunters broke open the bones to remove the marrow which was eaten fresh or used in soups. Marrow is high in calories and protein, so it was a highly valued food. The bones were saved to be made into sharp, strong tools.

Following the summer hunt, the people returned home with many tons of dried bison meat. If they were able to protect their supply of meat from raiders or military attack, they would eat well until the following spring.

This document is presented with permission of the Minnesota Historical Society and American Museum of Natural History. From Gilbert Wilson’s Reports, 1913, part 1, pgs 125-141.

Lakota Bison Hunt

The Lakotas lived in the woodlands east of the Great Plains where they lived as both hunters and farmers until around 1707.

The winter count of Battiste Good tells us that by 1707, the Lakotas had both horses and guns. They acquired guns and horses through trade networks that linked Indians to European Americans.

By the middle of the 18th century, the Lakotas were primarily bison hunters. They hunted for food and hides.

The surplus in hides was traded to other tribes or to Anglo-Americans for other things they needed. Women prepared the hides for trade by stretching and tanning the hides.

They also decorated the hides in order to get the best advantage in trade. In the late summer or early fall, Lakotas traveled to the Mandan villages to trade bison hides for corn which they needed for a good diet.

As the time for the communal hunt approached, the Lakotas began making plans. The hunt could not take place until a spiritual leader had a vision.

The vision might tell the people that the time to hunt was right, or it might tell them to wait a while. Either way, the people listened carefully to the advice and followed it.

After the proper spiritual ceremonies had been completed, the council met. The members smoked a pipe in the appropriate ceremonial manner and carefully discussed the hunt.

Lakotas lived in tipis that could be easily transported from one camp to another. This mobility suited their bison hunting economy. A small camp like this would have been set up near the place where the Lakotas were hunting bison. The people would work very quietly in a hunting camp. The tops of the tipis are dark with smoke from the cooking fires. SHSND 10190-84-01-16.

This man’s regalia, ceremonial clothing, reflects the spiritual importance the Lakotas gave to the bison. His headdress was made from the head and horns of a bison bull. The vest, wrist bands and ankle bands were made from bison hide. SHSND 1952-6244-01.

After the meat was removed from the bison carcass, it was hung to dry on a rack near a fire or in the sun. The dried meat could be stored for a long time. Some was pounded into powder and mixed with bison fat and berries to make the nutritious wasna or pemmican. SHSND 1952-7166.

They decided when and where the hunt would take place. The discussion might have lasted a few hours or several days. The council ended with a great feast prepared by the women of the village.

Before the hunt began, the council chose four young men to organize and maintain order in the hunt. These men were called akicitas (ah kee CHEE tahs) or marshals. Each of the marshals wore a special shirt and carried a feathered banner to signify his role. The akicitas controlled the camp and had the authority to punish anyone who disobeyed.

This Lakota woman demonstrated how to flesh a fresh hide. She is using a small hide, perhaps from a deer for her demonstration. However, her technique is the same as for a bison hide. The hide was stretched and staked to the ground. The woman used a bone scraping tool, wrapped in rawhide, to remove the fat, connective tissue and remaining muscle tissue from the hide. SHSND 0270-0110.

Before the hunt, women prepared to move the camp. They made repairs to the tipis, harnesses and clothing.

The men prepared their bows and arrows and bison hunting horses for the hunt. They also played a game called hehaka (heh HAH kah) which was a game of speed and accuracy that involved catching a hoop with a stick.

The entire village traveled between 10 and 25 miles each day. Even very small children, elderly people and those who were sick went with the village on the hunt. They stopped where there was enough water and wood for a good camp.

The people traveled close together and kept watch for enemies. The season for

the Lakotas’ hunt was the time when all tribes were out to hunt bison.

When the camp arrived at a place near the herd, the people, even children and dogs, had to be very quiet so the bison herd would not be frightened.

When the scouts discovered a herd, they returned to signal the hunters. Different signals meant different size herds. If the scout waved his robe, then spread it on the ground, it meant that he had seen a herd (Battiste Good Winter Count).

First, the Lakotas made an offering to the spirit of the bison. The camp herald went through camp calling everyone to make ready for the hunt.

At first light, the marshals led the hunters silently toward the herd and arranged them so each had a fair chance.

At the signal, the hunters galloped toward the herd, keeping low on their horses. The bison, not seeing humans, did not run until the hunters released their arrows.

The hunters tried to wound or kill as many as possible. They shot an arrow into the bison’s side or chest. An animal that was wounded, but not killed might turn and charge the hunter’s horse.

The hunter quickly left the first bison he shot and rode after another. They continued until the horses were exhausted or all the bison they wanted were killed.

If there was a white bison in the herd they made a special effort to kill it. White bison were rare and considered wakan (wah KAHN) or sacred.

A white bison robe made an extraordinary gift or offering. One of the bison carcasses, perhaps a white one, was sacrificed for a good hunt. The hide was removed from the carcass, but the remainder of the animal was left in the field as a sacrifice of thanks.

Each hunter identified the animals he had killed with some mark or piece of clothing. Soon the women arrived with horses and travois for carrying the hides, meat and other parts back to camp.

The hunters took a fresh liver, dipped it in gall (a bitter fluid from the gall bladder) and ate it. Lakota hunters believed that this food, eaten raw, gave them strength and courage. Roasted meat was served to the rest of the village.

Women now dried the meat, stored the fat and made wasna (WAHZ nah). They staked out the hides. The men rested.

After all the meat was dried and preserved, the tribe decided if they had enough for the winter or if they needed to conduct another hunt. If they did not need to hunt anymore, the marshals gave up their control of the camp and life returned to normal.

The Lakotas chose to live as nomads, hunting and trading, which provided them with a good living and a strong spiritual foundation. But this life demanded they be constantly prepared for an attack or war with enemies.

Bison provided everything necessary for a good life on the Great Plains. The Lakotas chose to live as nomads, hunting and trading, which provided them with a good living and a strong spiritual foundation.

However, this life also required that they be constantly prepared for an attack or war with enemies.

Ancient People used the atlatl, or throwing stick, to improve the speed, distance, and accuracy of the spear. An atlatl was a small stick, with a hook on one end. The end of the dart or spear rested on the hook. When the hunter threw the dart, he held onto the atlatl while releasing the dart. Around 3,000 years ago, hunters added a bannerstone (a stone weight) to the atlatl to improve the power and distance of the dart.

The Métis Bison Hunt

by Father Belcourt

1845, Father G. A. Belcourt went on a bison hunt with the Métis (MEH tee or MEH tees) people of the parish where he had established a mission 13 years earlier. Soon after the hunt, Belcourt wrote to a friend in Quebec (Canada) and described the hunt in great detail. Following is his description of the hunt.

“The hunters gathered at Pembina where the 55 hunters assembled a train of 213 carts, 300 horses and 100 oxen. Their families, 309 people in all, went along, too.

“Carts carried a thousand pounds of gear including firewood, lodge poles for their tipis, drying frames and hide stretchers, as well as food. They were heading into the ‘boundless prairies’ of Dakota where they would have to bring everything they needed, including firewood.

“Their route took them south of the Turtle Mountains towards Devils Lake, the Sheyenne River, and west toward Dogden Butte (Maison du Chien).

“Scouts traveled ahead on horseback looking for good places to hunt and camp. The scouts rejoined the main group in the evening, bringing information on bison herds ahead.”

Soon, two young men returned to camp with fresh bison meat. Father Belcourt was offered the tongue, a delicacy, rather than the meat of the bulls which was more abundant, but likely to cause “mal de boeuf,” or indigestion.

Metis hunters rode to the hunt with a loaded muzzle-loading gun and four more lead shot balls in their mouths. They re-loaded in the field by spitting the ball into the muzzle (front end) of the gun. Rapid re-loading meant that the hunters brought home more game and were able to protect themselves from charging bison bulls. Drawing by Vern Erickson, North Dakota History 38:3, page 340.

Using guns, the hunters fired into the herd, killing some animals and wounding others. A half-hour later, the hunt on this herd was over. “But a cloud of dust on the horizon signaled the presence of bison cows and the hunters took off after them.”

Women then skinned the carcass and removed the meat, fat, bones and organs that were useful to them. The meat was dried for long-term storage. The fat was mixed with powdered dried meat and dried berries to make pemmican.

In that year of 1845, when Father Belcourt attended the hunt, Metis hunters brought home the meat and by-products of 1,776 bison cows.

Once the bison cow or bull had been killed, it was set up on its stomach and the hind legs stretched out behind. Drawing by Vern Erickson, North Dakota History 38:3, page 344.

The hunters were excited and their well-trained horses wanted to charge into the cow herd, but approaching the cows was the most dangerous part of the hunt.

The hunters had to ride through the bulls that were bunched near the cows. If a bull gored a hunter’s horse and knocked the rider to the ground, the hunter might be killed by the bull’s horns or feet.

The Metis hunters carried muzzle-loading guns. They approached a herd with one shot prepared and carried 4 other balls of lead shot in their mouths.

They re-loaded their guns while riding their horses at great speed. They dropped the gunpowder into the muzzle and then spit a ball down the muzzle. A good hunter could load and shoot five times in the time it took to ride 100 yards.

On the first day, the hunters in Belcourt’s group killed 169 cows. In four days hunt, they killed and butchered 628 bison. By the end of the hunt, 1,776 cows had been killed.

Men and women worked together to butcher the carcass. After removing the hide, they took the hump (part of the back bone just below the neck) which was considered to have the best meat.

They also took the meat from the ribs and back bones, hips and shoulders. They removed the fat, the paunch or rumen (stomach), the kidneys, the bladder and the tongue.

The women cut the meat into strips about a quarter of an inch thick. These strips were hung on the drying frames for two or three days.

By then, the meat was so dry it could be rolled up and packed into large bundles.

Some of the less desirable pieces of dried meat were laid on a tanned hide and pounded into a powder. The meat powder was mixed with fat and poured into a rawhide bag called a taureaux (a French word for “bulls”). The mixture was called pemmican.

The Métis often added dried fruit into the mix. The resulting food was rich in nutrition and would keep almost indefinitely.

By the middle of October, the hunters were ready to pack for the return home.

The hunt resulted in 228 taureaux, 1,213 bales of dried meat, 166 sacks of fat (weighing 200 pounds each), and 556 bladders of marrow (12 pounds each).

Belcourt estimated the bison products to be worth £1700 ($218,179 today). The people had enough meat and pemmican for their winter food supply.

Father Belcourt concluded his letter with a commentary on the discipline of the hunt.

If a hunter started out alone, he might kill three cows and scare away the rest of the herd. He noted that in recent years, Métis hunts had lacked organization and leadership.

An organized, well-disciplined group of hunters could take 300 cows. Belcourt believed that religious leadership led to harmony and productivity on a bison hunt.

The Métis hunted bison in much the same way that their Chippewa relatives did, though they apparently lacked the tightly controlled organization that was necessary for a successful hunt.

Father Belcourt encouraged other priests to hunt with Métis of their parishes because, he believed, a priest could encourage the hunters to work well together.

Father Belcourt recorded an important part of Métis culture, and he also recorded the ways in which European American culture was bringing change to the people of the northern Great Plains.

Explorers and the Fur Trade

Fur traders entered the region that became North Dakota around 1800.

A few independent traders may have entered the region earlier, but Alexander Henry of Canada on the lower Red River (1799) and American Robert Dickson on Lake Traverse (1800) were the first to build trading posts that drew on the rich fur resources of eastern North Dakota.

The Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company competed with each other by building posts very close to one another.

They also tried to take business away from each other by offering better deals to their Indian trade partners.

Both companies engaged in over-trapping beavers to drive the other company out of the region. They succeeded in nearly destroying the beaver population of the region and in degrading the cultures of many Indian tribes.

Many smaller companies entered the fur trade, but most were eager to sell their business to a larger company after a year or two of tough competition.

In 1821, the beaver trade came to an end when European fashions in hats changed from felt made from beaver fur to silk.

The fur trade was both very good and very bad for American Indians who participated in the trade. The fur trade gave them steady and reliable access to manufactured goods, but the trade also forced them into dependency on European Americans and created an epidemic of alcoholism.

There is no doubt that knives with steel blades, iron cooking kettles, guns, hoes with metal blades and other manufactured goods made life a lot easier for Indians. Though the trade items saved time for Indian women, much of that time was now given to cleaning and stretching beaver pelts or bison hides. There was a shift in the household economies of Indian families that, at first, seemed to produce greater security and efficiency.

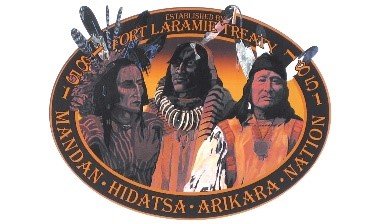

American Indians often re-made trade goods into something they found useful.

For instance, manufactured pipe stems made of bone were intended to be used with corncob pipes. However, the Poncas used the pipe stems as beads.

Quill work. Traditional decorations like this horse brow band were made from porcupine quills. In the early 1800s, traders brought dyes to the northern Great Plains and women began to dye quills to make beautiful designs. SHSND Museum collections, 1882.

Colorful glass beads were a common item in the fur trade. Native women used beads to achieve a high level of artistic expression.

Indians who traded with European Americans received all kinds of manufactured goods in exchange for furs. Indians sometimes re-used the goods in ways that better suited them. These leggings were made by a Lakota woman, Anne Good Eagle. She constructed the leggings with a cotton cloth flour sack from the Royal Milling Company and leather. She then decorated them with dyed porcupine quills. The leggings would have been tied around a woman’s legs. Only the decorated leather would show below her skirt. SHSND Museum collections. 1986.234.222

The style spread to the tribes of the northern Great Plains and they became very popular for use in elaborately decorated breastplates. The pipe stems came to be known as hair-pipe beads.

The young Dakota women in this picture are wearing breastplate necklaces made of bone hair pipe beads (light colored) and glass beads (dark colored). The hair pipe beads were originally designed to be pipe stems for corn cob pipes. Ponca Indians decided to use them as beads. The manufacturer, taking the new market into account, re-styled the hollow bone pieces as beads. The new use spread to the northern Plains where people of many tribes adopted the design. SHSND 0009-26.

Beautiful designs stitched in colored beads graced their clothing, their moccasins, and ceremonial goods such as pipe stems, blankets and saddle bags.

Women still decorated objects with porcupine quills, now colored with dyes they received in trade, but increasingly more items were decorated with intricate beadwork designs.

Though traders might have thought that glass beads were a cheap item to exchange for beaver pelts, women applied their special design skills in beadwork.

Some women were able to trade their beading skills with other members of their tribe for food, horses or other things they needed.

Indian women were important agents in the fur trade. Men usually trapped beavers, but women scraped the flesh off the fresh hide, stretched it and properly prepared the pelts for trade.

They often made the decisions about which company they would trade with. They also demanded the best rate of exchange.

They sometimes lost control of the trade when a trader, such as Alexander Henry, forced the trade to go in his direction.

During one visit to the Mandan villages, Henry fought with the women who owed their furs to the XY Company in payment for their debts. Henry finally won, but he had to force the women to give up the furs.

The women then had to acquire more furs (and work harder) to pay their debt to the XY traders.

Some Indian women chose to marry European American traders in the fashion of the country.

This generally meant that these marriages were not recognized by law or religion. While many marriages brought loving couples together for the rest of their lives, other marriages were short-lived.

The children of mixed marriages in the Red River region formed a new culture called Métis. The mixed-blood children of marriages in other tribes usually grew up with their mother’s people.

After successful buffalo hunting in the plains of Canada, Montana or Dakota Territory through the 1850s, long caravans of Metis often travelled on to St Paul or Winnipeg to trade buffalo products through the fur trade. These included hides, fresh meat, cured pemmican made of dried, pounded meat mixed with melted fat and fine beadwork which were exchanged for such needs and desires as tools, guns, ammunition, housewares, cloth, blankets, beads and alcohol. By 1880 plains bison were nearly gone from Canada and Montana, as well as having disappeared from the southern plains by 1875. The last herds were killed in what is now North and South Dakota in traditional hunts on the Great Sioux Reservation by Lakota and Dakota Sioux.

Father George Antoine Belcourt was a French Canadian priest who established missions among the Chippewas and Métis of the Red River and Turtle Mountains. His letter of 1845 on the bison hunt describes the method of the hunt and the processing and preserving of the meat and other parts of the bison. Father Belcourt’s letter also tells how European American culture was beginning to have an impact on Métis culture. SHSND 0986-04.

When they spotted a herd of bulls, Belcourt and a group of hunters approached to within 500 yards. They slowed their horses to a quiet walk so they could get near the animals without scaring them.

The bulls noticed the hunters and began to threaten them, stamping and tossing the earth with their horns. Other bulls watched the hunters and bellowed.

When they were close enough, a hunter gave the signal to ride their horses rapidly toward the herd. The bulls took off running “with surprising speed.”

This velvet vest was decorated with glass beads in a traditional Chippewa/Métis floral design. Glass beads were an important trade item. Indian women exchanged furs for glass beads and other manufactured goods. Glass beads were used to decorate clothing and other items. The most intricate designs were made for special occasions. SHSND Museum. Collections, 1987.84.1

Indian women were important agents in the fur trade. Native women scraped the flesh off the fresh hide, stretched it and properly prepared the pelts for trade. They often made the decisions about which company they would trade with. They also demanded the best rate of exchange.

Traders, especially those working for the NorthWest Company, often used liquor to persuade Indians to trade. Sometimes, liquor was used to cheat Indians out of their furs. Liquor diminished the capacity of American Indians to make good business decisions.

Indians and trappers who drank too much got into fights; sometimes the violence led to murder. Though U.S. law (and the Hudson’s Bay Company) prohibited the transport of intoxicating liquors into Indian country, it was difficult to enforce this law.

If an Army officer found liquor on a fur trade boat, he would destroy all of the kegs, but there were not enough officers to patrol river traffic.

Many relationships between traders and their Indian partners were friendly and respectful.

Indian tribes and fur companies enjoyed mutual benefits from the fur trade. Indians obtained manufactured goods such as guns, knives, cloth and beads that made their lives easier. The traders got furs, food and a way of life many of them enjoyed.

However, competition among the tribes and among the fur companies created more conflict than peace. In addition, the fur trade led to the destruction of individuals and tribes even after the fur business ended.

Fur traders gathered information about Indian country that drew farmers, miners and railroads to the northern Plains.

The people who followed the fur traders were usually most interested in taking land from Indians. The Native Americans’ ability to resist was diminished by alcohol, disease and dependency on trade goods, as well as broken treaties with the US government.

The fur trade was a business that made profits for the owners and many of the traders. But it was also a cultural meeting ground where all of the participants were on equal footing. Everyone had something of value to trade.

However, in the long run, the fur trade was also destructive for the American Indian tribes of this region.

Many people forgot traditional skills for making things such as knives or hoes that they could now purchase with furs. Traders brought deadly diseases to Indian communities.

Violent conflict often broke out between tribes that participated in the fur trade. There was some good in the fur trade, but often, the effects of the fur trade were not positive for American Indians.

The women gardened on river bottom land. Upland ground (where summer homes were built) was too hard and dry, but the river bottoms were soft and moist.

When the leaves emerged on the gooseberry plants, the women started to plant corn. This was in May; planting was not completed until June.

The gardens included sunflowers, beans, squash and tobacco in addition to corn.

The seeds were planted so that each plant could take advantage of the qualities of the other. Beans were planted near corn. Several varieties of squash were planted in the wide spaces between sections where different varieties of corn were planted. The broad leaves of squash shaded out the weeds.