Bison Meat: Delicious and Nutritious

First published Jan 26 2021.

“The meat that has ‘ping’ to it—the meat that satisfies.”

That is how Lakota hunters from the Cheyenne River Sioux tribe described the taste of buffalo to the missionary Thomas Riggs on the way to their last winter hunt in December of 1880.

For 15 years buffalo had been gone from their Great Sioux Reservation, due to settlement pressures from the east, but mysteriously they had returned and the older hunters were eager to taste their favorite meat again.

by Francie M. Berg

First published January 26, 2021

“The meat that has ‘ping’ to it—the meat that satisfies.”

That is how Lakota hunters from the Cheyenne River Sioux tribe described the taste of buffalo to the missionary Thomas Riggs on the way to their last winter hunt in December of 1880.

For 15 years buffalo had been gone from their Great Sioux Reservation, due to settlement pressures from the east, but mysteriously they had returned and the older hunters were eager to taste their favorite meat again.

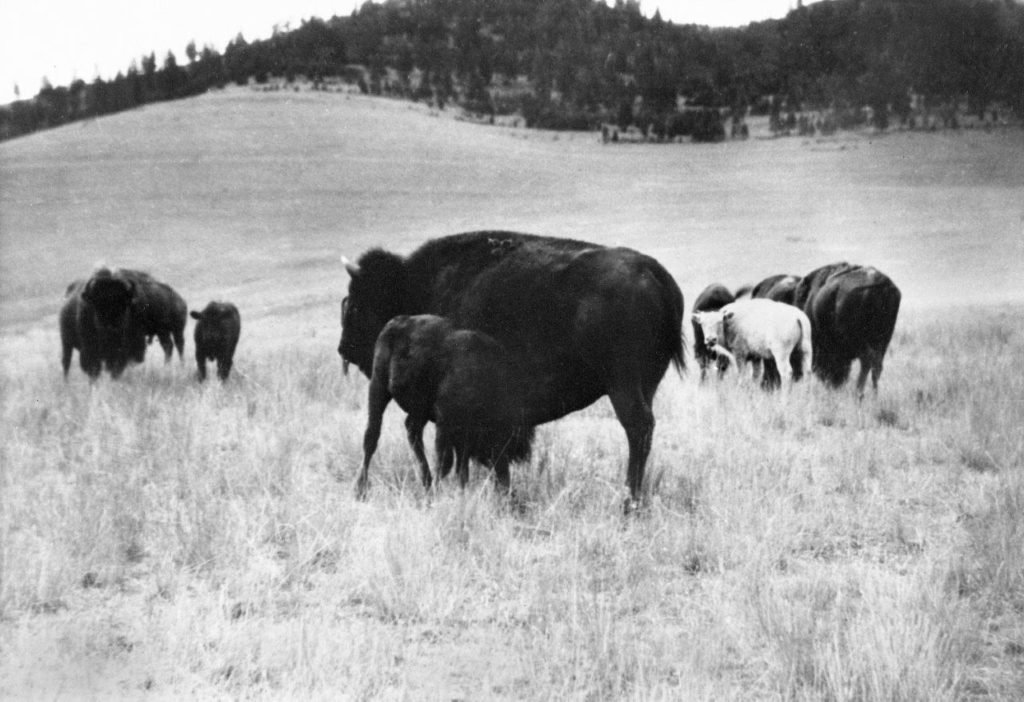

Snow fell almost continuously and the hunting party of 101—about half men and half women and children—followed the Moreau River valley west with buckboard wagons and extra pack horses. Some days they made only three or four miles in deep snow that crusted and grew deeper day by day.

The hunters grew excited that last day as they neared the Slim Buttes, where scouts told them the buffalo had returned.

They talked of how tired they were of eating porcupine, skunk, venison and badger meat. During their journey the party had killed and eaten 148 porcupines and 200 deer.

The Lakota also had brought 500 dogs as back-up if needed—but mostly to fatten up for later.

Then, on the day before Christmas, they made their first local buffalo hunt in 15 years.

The men returned to camp loaded with an abundance of meat and robes. The women helped unload and cared for the meat and hides.

Fires crackled, pots boiled. People ate the tasty buffalo meat with great relish. All were smiling and happy.

In fact they were so happy with the hunt and the meat that they stayed in the Slim Buttes hunting area in tepees and tents for 3 months—even though they had packed only enough provisions for 3 weeks and soon ran out of all other food.

From then on they had only fresh buffalo meat to eat—no vegetables, no tobacco, no coffee or tea, except what they made with rose hips.

But still they stayed—even through the coldest blizzards and deepest snow they had ever known—until they had all the buffalo meat and hides they could carry home again.

“Eat the meat of the buffalo. It’s healing. It keeps our people strong. It fills the soul as well as the body,” say Native Elders today.

Health-conscious people across the US and Canada have discovered the benefits of Bison meat today. They call it nutritious, hearty, sweet and rich, tasty and tender and nearly fat-free.

Speaking for myself, some of the best meat I ever tasted was at the 3-Day National Bison Association Summer Convention held in North Dakota in 2019.

We ate buffalo meat every day. Tender and tasty! Perfectly seasoned!

Much of the meat was donated by local producers as I remember—so they probably made sure it came from the best bison cuts, from bison of just the right age. No tough old bulls.

The Great American Buffalo Cookbook

The National Bison Association compiled and published a 22-page gem called “The Great American Buffalo Cookbook” in 2002. It’s organized for all cooks, those just getting started with cooking Bison as well as seasoned cooks.

Includes lots of good cooking tips, clearly explained. Everything you need for cooking delicious Buffalo Meals—and all for only $3.00.

You can order The Great American Buffalo Cookbook here: National Bison Assoc, 8690 Wolff Court, #200; Westminster CO 80031, or by visiting the website www.bisoncentral.com (Note: even more recipes are available on the NBA website.)

This cookbook is only 22 pages, but includes lots of good cooking tips, clearly explained.

(Note: Except for front and back covers, shown above, the colored food photos that illustrate this article are not included in the NBA Cookbook.)

Grilling Buffalo Steaks

Lots of “Hints” and “Tips” are included. The NBA Cookbook starts right out with the basics of grilling a Buffalo Steak.

Grilling Buffalo Steaks

Cooking time is important in order not to overcook your steaks. Total cooking time will depend on the thickness of the steaks.

1 inch thick Rare: 6-8 minutes Medium: 10-12 minutes

1 ½ inch thick Rare: 10-12 min Medium: 14-18 min

2 inch thick Rare: 14-20 min Medium: 20-25 min

Steaks recommended for grilling/barbecuing include Rib Eye, T-bones, New York Strip, Flat Iron, Flank and Sirloin.

Less tender cuts of buffalo steaks are not recommended for grilling unless they have been marinated.

Steaks thinner than ¾ inches thick are not recommended for barbecuing or broiling. (Note: Well-done buffalo steaks are not recommended. Due to the leanness of the meat, buffalo has a tendency to become dry when overcooked.)

Broiled Buffalo Steak

Rub your favorite cut of steak with a combination of a little garlic salt, cooking oil, ground black pepper and lemon juice. The lemon makes it tangy, with a zippy flavor.

Rosemary Marinated Steak

1 sirloin buffalo steak

1 Tbs. dried rosemary

½ cup red wine

¼ cup olive oil

Hints

For good cooking, preheat broiler or grill at least 5 min. before you broil or grill a steak.

Use long handled tongs to turn steaks on the grill. A fork will pierce the meat and allow the flavorful juices to escape.

Sear both sides of your steak on hot grill to keep the juices in the steak, then turn heat down and finish cooking to desired doneness.

When cutting thin slices of meat, have the whole piece slightly frozen. It will slice easier.

The cookbook is divided into 4 sections, with 6 to 10 recipes in each:

1. Steak and recipes using meat chunks, cubes or slices. Includes Buffalo Fajitas, Pita Pockets, Kabobs, Stew and Stir-Fry.

2. Buffalo Roast and Leftovers, includes Bar-B-que Buffalo, Crock Pot, Buffritos, Sandwich Filling.

3. Ground Buffalo and Buff A Loaf, Buff-N-Biscuit, Chicken-Fried Steak, Meatballs, Lasagna, Cheeseburger Pie, Buffalo Quiche and Chili.

4. Miscellaneous (Buffalo salami, tongue, heart, more).

Further it is noted that Buffalo may be used with any of your favorite beef recipes if you remember these basic tips.

Buffalo Cooking Tips

Buffalo meat is similar to beef and is cooked in much the same way. The taste is often indistinguishable from beef, although buffalo tends to have a fuller, richer (and sweeter) flavor. It is not “gamy’ or wild tasting. Buffalo is low in fat and cholesterol, and is high in protein, vitamins and minerals. Fresh cut buffalo meat tends to be darker red and richer in color than many of the other red meats.

The lack of fat ensures that buffalo meat will cook faster. Fat acts as an insulator—heat must first penetrate this insulation before the cooking process begins. Marbling (fat within the muscle) aids in slowing down the cooking process. Since buffalo meat lacks marbling, the meat has a tendency to cook more rapidly. Caution must be taken to ensure that you do not overcook buffalo.

When oven broiling buffalo, move your broiler rack away from the heat about a notch lower from where you normally broil your beef steaks. Check your steaks a few minutes sooner than you normally would.

If you normally cook your roast beef at 325 F, turn your temperature down to around 275 F for buffalo. Plan on the roast being done in about the same amount of time as with a comparable sized beef roast. To ensure the temperature you prefer, we recommend using a meat thermometer indicating the internal temperature.

Ground buffalo or Buffalo burger is also leaner (most ranging about 88-92% lean). It will also cook faster so precautions must be taken not to dry out the meat. There is very little (if any) shrinkage with buffalo burger—what you put in the pan raw will be close to the same amount after you cook it. Pre-formed patties tend to dry out faster when grilling. (Hint: the thicker the patty, the juicier the burger.) Although ground buffalo is leaner, there is no need to add fat to keep it from sticking to the pan or falling apart.

All meat, no matter the leanness has enough fat available to cook with it properly. The great thing about ground buffalo is you don’t need to drain off any grease from the pan!

Award Winning Bison Recipes from NBA

Additional Bison recipes are available at www.bisoncentral.com

Here are some award winners selected by NBA and on their website.

This is an especially good one. For the dedicated chef, I think.

Irish Creek Ranch Best Slider, Winning “Best Bison Slider” Recipe from the NBA’s 2017 Winter Conference.

First Place Bison Burger Slider Recipe, by Karissa Dorey

Irish Creek Ranch Favorite Sliders.

Vermilion, Alberta Bison burgers are something that even the most unlearned, uncultured taste buds can enjoy. (For those of you who believe bison taste “gamey!”)

It is a sure staple on our ranch. Everyone loves it.

My husband every time repeatedly exclaims whilst sinking his teeth into this juicy burger, “This is amazing. People would pay a lot of money for this!”

Hands down this is the BEST burger ever. And maybe even the best BISON burger!

All this being said it is possible to totally screw up a bison burger.

So follow the instructions—especially the burger patty frying part and cover that frying pan!

Irish Creek Ranch Favorite Sliders

Makes: 8 -1/4 lb slider patties

Burger Patties:

2 lbs Ground Bison, thawed

Montreal Steak Seasoning

Worcestershire Sauce

3 Tablespoons Canola Oil

Whiskey Caramelized Onions:

2 Sweet onions

3 Tablespoons Olive oil

8 Brown mushrooms

2 Tablespoons Whiskey

8 slices of Gruyere cheese

8 slices of bacon

8 sourdough slider buns

4 handfuls of arugula

Truffle Aioli Sauce:

3 cloves garlic, minced

1/2 lemon, juice

1 cup mayonnaise

3 Tablespoons Truffle oil

2 Tablespoons Dijon mustard

Instructions:

First prepare onions 1 hour in advance:

Cut onions thinly. Place in frying pan over med-high heat, cover and cook onions and oil till

translucent. Take lid off and cook on low for 1 1/2 hour—be sure there is a single layer of onions on bottom of pan. Periodically stir to prevent burning. In the last 15 mins add mushrooms. Let cook. Then in the last 5 mins add whiskey.

Truffle Aioli Sauce:

Stir together all ingredients. Set aside

Bacon:

Cook bacon in advance for about 30 mins in the oven at 375 F. (Cook in a pan with sides lined with parchment paper.)

Burger patties:

Form 8 equal patties. Do not over handle. Sprinkle seasoning and Worcestershire sauce over each burger. Brush canola oil over each burger. Over high heat, heat remaining oil in a large frying pan. Once oil is hot (500 F) place burgers oil side and seasoning side down. Cover pan and cook for 4 mins. Flip and cook for additional 3 mins or until burger patties reach 140 F.

Let sit for 5 to 10 min before serving. Place caramelized onions/mushrooms and then bacon and then cheese over each burger. Cover and cook for additional 1-2 minutes or until cheese is melted.

Place on a freshly toasted bun smeared with Truffle Aioli sauce and arugula or lettuce. Stack from bottom to top: bottom bun, aioli sauce, lettuce, burger, onion/mushroom, cheese, bacon, aioli, top bun. Serve with fresh oven baked sweet potato fries and/or salad.

Karissa Dorey, Irish Creek Bison.

Other winners:

Canadian Prairie Bison Chili, Winner of “Best Bison Chili” Recipe from the NBA’s 2018 Winter Conference.

Colorful Bison Chili, Hawkeye Buffalo Ranch, Runner Up for “Best Bison Chili” Recipe from the NBA’s 2018 Winter Conference.

Sweet and Smoky Island Slider, Runner Up Slider Recipe from the “Best Bison Slider Recipe” Contest

Southwest Bison Pho, by Benjamin Lee Bison—2020 NBA Winter Conference Recipe Winner.

Truly Saskatchewan Bison Stew, Winner 2019 NBA Winter Conference Best Bison Stew.

Bison Blue Cheeseburger

Serves 6

Kathy Cary, Lilly’s, Louisville, Kentucky

Food Photography Jason McConathy

Recipe styling: Cook Street School of Fine Cooking—Denver, Co

INGREDIENTS

1 1/2 lbs. ground bison

1 Tbs. good quality Dijon mustard

2 Tbs. roasted & chopped shallots & garlic

1 tsp. Lea & Perrins Worcestershire sauce

Splash extra virgin olive oil

Kosher salt & fresh ground black pepper to taste

Good quality blue cheese or Roquefort

2 red onions sliced

Balsamic vinegar

2 bulbs fennel sliced

DIRECTIONS

Combine first 6 ingredients and form 6 patties, adding approximately 1 teaspoon of blue cheese into the center of each patty. Grill to order.

GARNISH

2 sliced red onions drizzled with extra virgin olive oil & balsamic vinegar.

Grill until tender.

2 bulbs of fennel, sliced & sautéed until tender.

Toss the onions & fennel together and place on bison burger

Serve with rosemary roasted potatoes and homemade coleslaw.

Bison: High in Protein, Low Fat, Low Cholesterol

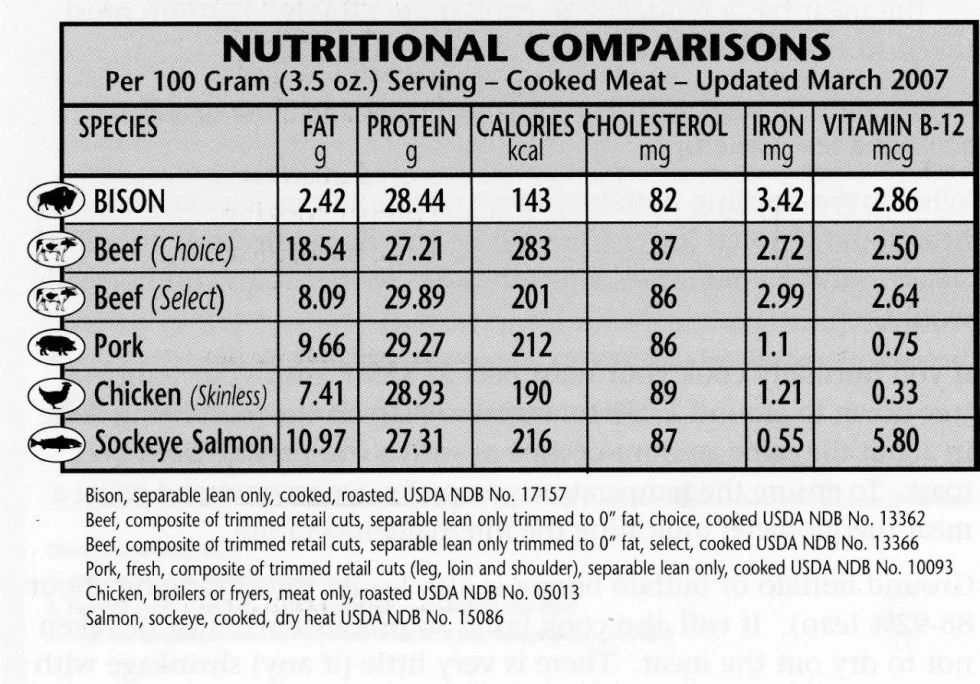

Research from Dr. Marty Marchello of our own North Dakota State University is included in the NBA Cookbook—so you can see how Bison compares nutritionally with beef and other meats. His USDA research was done at NDSU in 1996, updated in 2007 and 2013.

Below are Dr. Marchello’s nutritional comparisons for fat, protein, calories, cholesterol, iron and vitamin B-12 of 100 grams of cooked meat (a 3.5 oz serving) from Bison, Beef (both choice and select), Pork, Chicken and Sockeye Salmon.

Dr. Marty Marchello’s nutrition chart compares the fat, protein, calories, cholesterol, iron and vitamin B-12 of 100 grams of cooked Bison meat (a 3.5 oz serving) to that of choice and select Beef, Pork, Chicken and Sockeye Salmon. NDSU.

At the August 2002 meeting of the Missouri Bison Association, Professor Barbara Lohse (Knouse), PHD, RD, LD, a Dietitian from Kansas State University spoke about the nutritional value of Bison meat.

Dr. Lohse, now Associate Professor and Principal Investigator at Pennsylvania State University, said there are many important advantages to bison meat in addition to the well-known “High in Protein, Low in Fat and Low in Cholesterol.”

This is especially important during this time when more people are pursuing healthier nutritional lifestyles, she said.

Dr. Lohse highlighted the following advantages of Bison nutrition:

B6 and B12 (Bison is a HIGH source of these vitamins)

Vitamin B12 is only available from animal sources

Vitamin B12 has been shown to keep the elderly mentally alert

Vitamin B6 is needed for protein metabolism

Sodium (Bison is a LOW source of Sodium)

High sodium intake is associated with hypertension

Potassium (Bison is a HIGH source of Potassium)

Key to lowering Blood Pressure

Most foods high in potassium are also high in calories

Bison contains 1/3 more potassium than chicken

Iron (Bison is a HIGH source of available Iron)

Necessary for hemoglobin formation and prevention of anemia.

Bison is 3 times higher in Iron than pork or chicken.

Selenium (Bison is a HIGH source of Selenium)

An antioxidant shown to help prevent cancer.

Bison has 4 times higher amount of Selenium than the USDA recommends as an antioxidant

Conjugated Linoleic Acid (Bison is a high source of CLA)

Antioxidant that has been shown to help prevent cancer

Calories (Bison is a LOW source of calories) 1/2 the calories of pork and chicken

Ranch to Table: The buffalo meat market

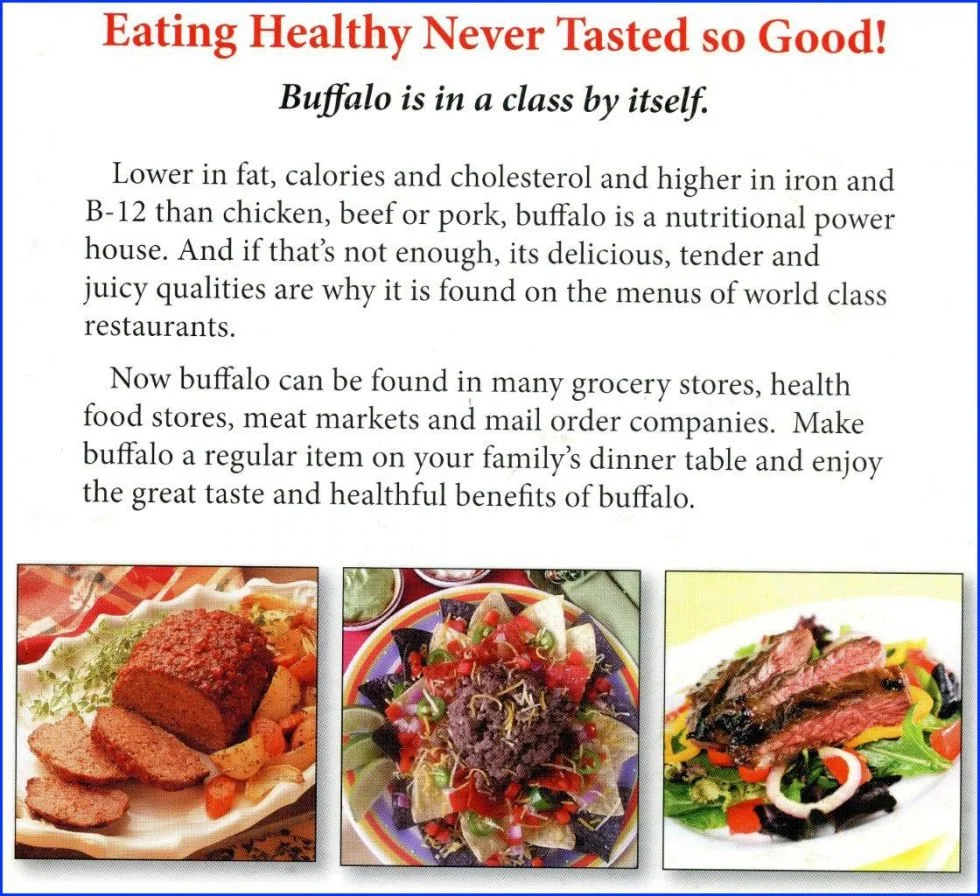

“Now buffalo can be found in many grocery stores, health food stores, meat markets and mail order companies. Make buffalo a regular item on your family’s dinner table and enjoy the great taste and healthful benefits of buffalo,” says the NBA website.

Also available on the NBA website is a list of producers who sell and ship Bison meat.

Beware of Water Buffalo Masking as American Bison

In her presentation Dr. Lohse emphasized the big differences between meat from American Bison (Bison) and Water Buffalo originating in Asia or Africa—recently being sold in the United States. Packages are often designed to resemble homegrown Bison.

In NUTRITION CHARTS she notes that American Bison meat is labeled “Bison,” not “Buffalo.” If you purchase meat labelled “Buffalo” it is probably imported water buffalo.

The NBA Cookbook, published earlier, doesn’t mention this. It can be a bit confusing because the Cookbook calls for “Buffalo” in its recipes. (Just remember Dr Lohse’s tip above when purchasing meat. Otherwise, we accept the terms as interchangeable.)

Don’t make the mistake of buying Buffalo meat unless it’s labelled “Bison.”

Note that buffalo today are butchered young—at 2-3 years of age—while they are tender and tasty. In addition buyers often have the choice whether to buy grass-fed or grain finished bison meat—which is a bit higher in fat, preferred by some. Many other health-conscious customers prefer and enjoy grass-fed bison meat.

It’s not like old days when the big old bulls were easiest to shoot, running on the outside of a stampeding herd to protect the more tender and tasty young bulls and cows running farther inside.

Native American hunters knew this and found a way to get past the old bulls, to the more tender and well-flavored young bulls and cows. In our histories they often told of how they’d shoot several bulls running on the outside of the herd to get past them and reach the more tender—and tasty—young bulls and cows being protected there.

Only if a hunter wanted a special trophy head, or huge tough hides for covering the tepee did he settle for older bulls. Likely, tenderness was less of a concern when their meat was dried for making jerky or pemmican.

Native Americans Love and revere the taste

Today, with their own tribal herds—no question, the opportunity to again eat buffalo meat is cherished by Native Americans.

They love and revere the taste of real Bison meat.

Tribes with buffalo herds use much of their own buffalo meat within the community.

Butchering and caring for the meat is regarded as an integral part of the circle of life, and as an important skill to teach children.

“We take our children to the kill,” explains LaDonna Allard, Tribal Historian for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

“The process is carried out with due ceremony, with prayer and thanksgiving,” she says. “We thank the buffalo.”

A high-powered rifle takes down the animal, so it is killed instantly to alleviate suffering.

The carcass is then skinned and cut up in traditional ways, with all parts used in ceremonies—horns, skulls, bones and hides.

“Every part has meaning. We use them all,” Allard explains.

The Fort Peck tribes in Northeastern Montana have built their own butchering facility, out near the corrals, for tribal members who want to purchase and slaughter their own buffalo from the business herd of about 200 head.

Robert Magnan, Fort Peck Fish and Game Director, says he buys a buffalo himself each year and shares it with relatives, as do around three dozen other tribal members.

“We have all the equipment—saws, grinder—and they bring their own wrap. We teach them how to cut up the different parts—roast, steaks. Grind the tougher cuts and scraps for hamburger. [We teach] how to cook them.”

But first, says Magnan, echoing what others explain, “We talk to the buffalo. Tell them we need meat to feed our families. Thank them for their willingness to take care of us.”

For meat used in the tribes’ federally subsidized programs the Ft Peck tribes haul live animals to the nearby small town of Scobey, where they are processed in a USDA meat inspected plant.

A buffalo carries less meat than a steer, he says, about 800 pounds on the carcass.

The Fort Peck tribes offer buffalo hunts, as many as 40 or 50 a year from their business herd.

In 2014 hunters paid the tribe $850 for a two-year-old bull, $1,200 for a dry cow, $1,500 for an ordinary bull, and up to $10,000 for a big bull with well-formed horns.

Many are return hunters who come from foreign countries—Korea and Germany—and Texas and other states throughout the US.

Magnan’s staff instructs hunters to wait until they can shoot an animal off by itself—one of the five or six in a pasture with blue ear tags, designated for paid hunting. They are told not to fire into the herd.

Magnan insists the selected buffalo needs to be put down quickly without suffering. He goes with the hunter and carries a rifle to finish the job himself if the paying hunter only wounds it.

In many tribes, anyone putting on a community feed can request buffalo meat.

Buffalo is served at graduations, namings and community celebrations, and has become an honored part of the healthy foods in diabetes programs.

Because buffalo meat is low in fat and cholesterol and high in protein, highly absorbable iron and zinc, and is considered delicious and exceptionally healthy, it is welcomed as a healthy food. When grass fed, it is even more nutrient-dense.

Diabetes is a serious concern in many Indian tribes.

Tribal leaders attribute their higher diabetes risk to genetics and reservation living, which often leads to a sedentary lifestyle and diet high in sugar and fat.

Today’s lifestyles are quite unlike the traditionally active lifestyles and lean, high protein diets of 100 years ago.

“Buffalo meat, grass fed meat—this is something people with diabetes can eat that is good for them,” Alvah Quinn explains in talks at schools.

“We can offer 100 percent pure buffalo meat to our tribal members for nothing or almost nothing. With all the diabetes in Indian Country, eating right is important.”

ITBC, 30 years — Yellowstone Bison Dilemma — Part 2

January 10, 2026

From the time he learned of it, Robert “Robbie” Magnan director of the Fort Peck Fish and Wildlife Department in northeastern Montana was troubled by the annual buffalo slaughter of excess buffalo in Yellowstone Park.

by Francie M. Berg

From the time he learned of it, Robert “Robbie” Magnan director of the Fort Peck Fish and Wildlife Department in northeastern Montana was troubled by the annual buffalo slaughter of excess buffalo in Yellowstone Park.

It was not enough that the bison meat was distributed to Indian tribes in neat frozen packages.

Magnan and other founding members of the InterTribal Buffalo Council (ITBC) cherished the Yellowstone Park genetics that had flowed from free-roaming bison for more than a hundred years. They wanted those genetics in their own tribal herds.

Not quite the same as “always having lived wild” in Yellowstone Park. They knew that only a reported 23 buffalo survived poaching in the Park—back in the 1890s—and the wild Yellowstone pastures had been replenished by relatively tame buffalo from half a dozen sources, both US and Canadian. So not many were actually “pure.”

Still, the Yellowstone buffalo are special and many Native people deeply desire those genetics in their tribal buffalo herds.

The target population in Yellowstone Park is 3,000 buffalo, no more. But with new calves growing up in the herd it can quickly balloon up to 5,000 or more.

Because of the risks of spreading brucellosis to cattle herds, Montana law says that no bison can leave Yellowstone Park alive.

According to Montana Game and Fish, half the bison and elk in the Park test positive for brucellosis.

Hence, the surplus gets butchered, except for a few tribes allowed to come hunt at the borders in honor of ancient treaties that promised hunting rights.

One of the original founders of ITBC, Magnan has advocated to halt the slaughter of Yellowstone buffalo since 1992.

Two years later, in 1994, ITBC presented their first quarantine proposal to Yellowstone National Park, offering land and resources to support the development of quarantine facilities.

Over the years, Magnan often received bison meat for his tribe from this surplus.

Still, it rankled—even though the Park was 400 miles away, on a diagonal across Montana from his Sioux and Assiniboine Indian Reservation at Fort Peck.

Traveling the Big Pasture

But this was a gorgeous July morning in northeastern Montana. Problems created by winter overpopulation of Yellowstone Park buffalo seem far away.

Sweet breezes waft across the flat between the higher bluffs and the badlands below as Robbie Magnan heads his pickup farther north into the large quarantine pasture.

I was privileged to ride along over the green hills that summer morning in 2014.

Below us to the south we could see bits of the silver ribbon that was the mighty Missouri River—flowing east as it does through most of Montana.

We were looking for the 39 buffalo from Yellowstone Park that recently came to live in this generous pasture—about 20 square miles (equal to a rugged chunk of land four miles by five)—13,000 acres.

They have lots of space to roam and might be anywhere—up on the grassy plateau or down one of many gravel and juniper draws.

Magnan says this herd of buffalo often walk 8 or 10 miles a day while grazing.

They keep moving, so he never knows where to find them.

“I promised I’d look at them every day and that’s what I do.”

He chuckles and you know there’s nothing he enjoys more than bouncing over the grassy flats, up and over the dam and out on a high point of land each morning to scan the badland draws below for the little Yellowstone Park herd.

It was one step in an ambitious experimental program, and Robbie Magnan is an important link in the quarantine process.

He checks levels in a new water tank and the new, higher and stronger quarantine fence being built within the quarantine pasture for later Yellowstone Park arrivals.

It’s a well-fortified 320-acre pasture within a pasture—for extra security.

As we bounced over the terrain—sometimes on a dirt road or trail, sometimes straight across the prairie, up and down—Robbie tells me the amazing story of this small priceless buffalo herd and the quarantine research that brought it here.

The scientific research, still ongoing, studies whether Yellowstone Park buffalo that test negative for brucellosis as calves can continue to live disease-free.

The goal is to grow this very special herd and then, if still disease free, establish them in a wider area, where they can live and multiply on tribal lands outside the Park.

Magnan is pleased with his new six-wire buffalo-tight wildlife exterior fences—a smooth wire on top and bottom for deer to jump over and antelope to crawl under, with four taut barbed wires in between.

“As long as they have grass like this, water and the minerals they need—and we test the soils for that— they’ll stay in,” he says.

If not, they’ll go looking for what’s missing.

“We call them wide-ranging, not free-ranging like in Yellowstone. It’s not realistic to think buffalo will ever be free-ranging without fencing. They will always be in a fence.”

This lovely summer morning Magnan drives over two hours searching for the Yellowstone herd.

“Just one more place to look!”

We bounce over the next hill, down a grassy draw—and sure enough, there they are.

Magnificent, extra-large, extra-dark beauties, 39 young adults.

All these animals are the same age, since they were placed in quarantine as calves in Yellowstone Park, lived there several years before coming to Ft. Peck. Annually they have tested negative for brucellosis.

Although these buffalo are not family, because they were selected for diverse genetics, they have formed a tight family group.

They now have 12 calves and bunch together as they graze.

Curious and friendly, several walk over to surround the pickup, to sniff at us and grunt their greetings for a few minutes. A magical interchange.

Looking for treats, I thought. But they didn’t get any and moved on.

Best of all, there’s a new baby calf, born this morning.

The older calves are turning dark, the crests of their heads nearly black between little nubs of black horns, as it’s already mid-summer.

But this newborn baby is pure red-gold. He shines bright as a shiny new penny in the morning sun.

Magnan has hopes of increasing this cultural herd enough to achieve a natural diversity with a self-sustaining genetic base.

He has worked with the Fort Peck Fish and Wildlife for 20 years, 17 of them with their tribal buffalo herds.

“From the beginning of time, the buffalo have taken care of Native Americans. Now they need our help,” he explains.

In the distance, in another pasture, we glimpse a hundred or so of the Ft. Peck tribes’ other buffalo herd filing down a long hill to water.

Magnan calls the Yellowstone Park buffalo our cultural herd and the others—over there—our business herd.

He waves toward the buffalo surrounding us. These buffalo know him well. They also know his pickup.

“To us these are extremely valuable, like registered cattle. They’ll never be sold. We’ll use them only for cultural purposes.”

As we watched the Yellowstone herd, they spread out a bit, grazing, while several calves take the opportunity to nurse.

Then, still grazing, the herd comes together in a small, compact band and moves on up the green draw around a rocky point out of sight.

“The money we generate from our business herd is to take care of our cultural herd. This is a way we could feed our people if the social programs were stopped.”

One problem that concerns Robbie Magnan: none of these buffalo grew up in a multi-generational herd—since they were separated from their mothers and quarantined together as calves.

He wonders: How will they learn the wisdom of the herd? How will they understand the complexities of normal buffalo relationships?

However, so far the quarantine is working. No brucellosis outbreaks with these maturing young buffalo.

And Magnan and his staff have shown themselves capable. None have escaped.

Then it came time to relocate an additional 145 buffalo.

These were held five years in quarantine on Ted Turner’s Green Ranch near Bozeman—and before that in Yellowstone Park quarantine at Stephens Creek in the northwest corner of Yellowstone National Park—where they’d been captured and held in quarantine.

Montana authorities declared it too soon to divide them among the various entities, as planned. So instead they trucked them to Fort Peck’s quarantine pastures.

Robbie Mangan’s buffalo crew took over managing both Yellowstone herds.

“I enjoy them,” he says. “After 16 years they are still teaching me.”

The local press was on hand when the new herd arrived from Yellowstone Park at the Ft. Peck pasture. It was already dark.

As trucks rolled across the bridge leading to the release site near Poplar, a group of Assiniboine people stood waiting, singing a welcome.

An unforgettable moment for those on the bridge.

“We sang for them—a buffalo song,” said Larry Wetsit, vice president of community services at Fort Peck Community College.

“It’s a special day. Our people have been waiting and praying about this.”

During early reservation days hundreds of tribal members had starved, including his own ancestors, Wetsit said.

“It was all about having no buffalo. That was the low part in our history, the lowest we could go. This is a road to recovery.”

Larry Schweiger, president of the National Wildlife Federation, one of the agencies involved in the Interagency Bison Management Plan for dealing with Yellowstone Park brucellosis problems, was there for the release.

“We believe it’s the right thing to do for wildlife. It’s the right thing to do for the tribes. And ultimately the right thing to do for the landscape,” he said.

“What this means to me is the return of prosperity to our people,” said Wetsit.

An Assiniboine, Wetsit has been the medicine lodge keeper for over 20 years, a ceremony he learned as a young man.

“It’s a celebration of our life with the buffalo.

“What we’ve always been told, always prayed about, is that the buffalo represents prosperity. When times were good it was because our Creator gave us more buffalo.”

Iris Grey Bull, a Sioux member—the Fort Peck reservation is home to both Assiniboine and Sioux tribes—spoke about their close ties to the buffalo.

“The waters of our reservation form the shapes of buffalo,” she said. “One male is to the east and four females to the west.

‘Now they’re bringing back the buffalo. This is a historic moment for us. We’re rebuilding our lives. We’re healing from historical trauma.”

“I watched the bison come out of the trailers,” Schweiger recalled. “I was watching the faces of tribal elders and the women and children watching these big animals charge out of the trailers.

Homecoming on Tribal Lands

“I was so moved to see the reaction—a powerful thing to witness. After the animals were released the drummers sang a blessing. The snow was blowing,” said Schweiger.

“It was cold. It was dark. But there was a lot of warmth.”

On August 22, 2013, the remaining 34 buffalo of the same pure Yellowstone Park strain as those at Fort Peck were released on nearby Fort Belknap Reservation.

Montana’s governor Brian Schweitzer called the event a historic opportunity to bring genetically pure buffalo to this special place on the planet.

“These are the bison that will be breeding stock to re-populate the entire western United States, in every place that people desire to have them,” he said.

Gathered to welcome them with a pipe ceremony were 150 people.

“It’s a great day for Indians and Indian country,” announced Mark Azure, who heads the Fort Belknap tribe’s buffalo program.

The last two big bulls flipped up their tails and ran from the trailer to join the herd.

Mike Fox, Belknap’s tribal councilman, said the tribe’s goal is to manage the special buffalo herd and use it as seed stock for other places wanting to reintroduce the Yellowstone strain.

“It’s a homecoming for them,” Fox said. “They took care of us and now it’s time for us to take care of them.”

Robbie Magnan waited, his most prized herd was not allowed to travel to other tribes, as was planned.

Film: Return of the Native: 25 Year ITBC History

A wonderful film was made on the history of ITBC. I know our readers will enjoy it when you have time to check it out. Narrated by Mark Azure of the Fort Belknap tribe in Montana.

In this documentary you’ll learn more about the groundbreaking work that Tribal leaders have done to restore buffalo to Indian Country. It’s split into 3 parts—close to an hour long.

Also you may want to watch the related short video: ITBC’s “Returning the Buffalo.”

But on a rather sad note, the film ends with Robbie Magnan standing a lonely vigil by his empty quarantine pasture—320 acres. Enclosed by walls of 8-foot high woven-wire fences and inside that is a 2-wire electric fence strung within the perimeter.

Well barricaded against escape, but empty and silent.

After 2014 no buffalo came from Yellowstone to his quarantine pasture for years.

Progress was stalled while cattlemen protested the quarantine system in Montana courts. They remained concerned about losing their brucellosis-free status again—which would prevent them from selling their cattle.

Introducing the Indian Buffalo Management Act

Meanwhile new legislation called The Indian Buffalo Management Act was introduced in 2019 by Congressman Don Young (R-Alaska) to assure regular funding for the buffalo restorations programs in Indian country.

It was unanimously approved and passed out of the House Natural Resources Committee but did not make it to a vote in the 116th Congress.

According to his office, Congressman Young would likely need to reintroduce the bill in the 117th Congress. He pledged to continue working with tribal leaders, state and local partners, and other advocates to ensure that herds of these majestic creatures can be restored to their historical sizes.

“For hundreds of years, the American buffalo was central to the culture, spiritual wellbeing, and livelihoods of our nation’s Indigenous peoples,” said Congressman Young.

“The tragic decimation of these iconic animals remains one of the darkest chapters in America’s history, and we must be doing all that we can to reverse the damage done not only to the American buffalo, but to the way of life of Native peoples across our country.

“I am proud to be joined by Congresswoman Deb Haaland and Congressman Tom Cole, in addition to Alaska Native and American Indian organizations and countless tribes, as we introduce this critical legislation to protect a resource vital to Native cultural, spiritual, and subsistence traditions.

“I would like to thank the InterTribal Buffalo Council, in particular, for their advocacy and hard work on the development of this legislation. This bill is an important step to restoring once-vibrant buffalo herds, and I will keep working with friends on both sides of the aisle to see this legislation across the finish line.”

“The Pueblo of Taos greatly appreciates Congresswoman Deb Haaland’s support of reintroduction of Buffalo to Indian lands through her co-sponsorship of the Indian Buffalo Management Act,” said Pueblo of Taos leadership.

“This Act will allow the Pueblos of New Mexico to enhance existing herds, start new herds, reintroduce buffalo into Native population diets and generate critical tribal revenue through marketing.”

“When it becomes law, the Indian Buffalo Management Act will strengthen the federal-tribal partnership in growing buffalo herds across the country and in the process restore this majestic animal to a central place in the lives of Indian people,” said John L. Berrey, the Chairman of the Quapaw Nation of Oklahoma.

40 Bulls shipped to 16 Tribal herds

Then in August 2020 transfers were announced for 40 young Fort Peck buffalo bulls declared brucellosis-free by the state of Montana and the US Department of Agriculture.

At last, they were cleared for travel and slated for donation to 16 buffalo tribal herds in nine states.

Fifteen bulls were sent out to the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe, Prairie Band Potawatomi, Modoc, Quapaw, Cherokee and Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes.

A few days later more bison were hauled to the Blackfeet, Kalispell Tribe, Shoshone Bannock Tribes, Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, Oglala Sioux Tribe, Forest County Potawatomi and Oneida.

Logistics for two more tribes were still being worked out.

Arnell Abold, an enrolled member of the Oglala Lakota Sioux Tribe, is the InterTribal Buffalo Council’s Executive Director. She says this moment is a celebration for tribes, the National Park Service and the state of Montana.

“This is huge for us, and we’re eternally grateful and humbled by this moment, and we look forward to putting more animals back on the landscape and returning them to their homeland,” Abold said.

Megan Davenport is a wildlife biologist with InterTribal Buffalo Council.

“Tribes have been advocating for the last 30 years, particularly with this Yellowstone issue, that there’s a better alternative to slaughter,” Davenport said.

These animals marked the second transfer of bison from the Fort Peck Indian Reservation’s quarantine facility to other tribes, she said. The first was five bison sent to the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming.

On Dec 12, 2020, Ervin Carlson, of the Blackfeet tribe in western Montana, writing for ITBC as board president, reported on how it all this came about.

“It’s been 27 years since ITBC submitted the first proposals to quarantine and transfer Yellowstone buffalo as an alternative to their slaughter,” he said.

“It’s been only four months since this has been actualized, with the first tribe-to-tribe transfer of 40 brucellosis-free Yellowstone bulls sent from Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes’ quarantine facility to 15 native nations through ITBC.

“While this is a massive victory and testament to 30 years of inter-tribal efforts to protect the Yellowstone buffalo, it has not been achieved without significant challenge.

He explains that in 1992 tribes were denied a seat at the table in the process of drafting the environmental impact statement for considering management alternatives for Yellowstone buffalo.

“Despite denied participation, ITBC persisted, introducing proposals and resources to develop a quarantine program.”

In 1997 ITBC submitted their first proposals to build quarantine facilities on tribal lands.

“This achieved overwhelming support from public citizens, nonprofits and federal agencies, though roadblocks persisted.

“ITBC finally won a seat at the Interagency Bison Management Plan in 2009 to protect and preserve the Yellowstone buffalo.”

“Due to the dedication of the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux tribes, and the 30 years of arduous activism by ITBC, the tribes completed construction of their quarantine facility in 2014.

“This facility was built to accommodate all phases of quarantine and can handle approximately 600 buffalo on 280 acres surrounded by double fences.

“With the assistance of ITBC, the tribes continue to improve this facility by expanding the number of pastures through cross fencing, increasing the capacity for additional groups of buffalo.

“The construction of this facility was initiated upon the request of the National Park Service.

“The Fort Peck quarantine facility is still not used to its full potential because a Montana law and federal regulations are misapplied to the tribes.

“The capacity of the facilities in and near the Park are not adequate to allow new groups to enter the quarantine program each year resulting in a larger number of buffalo being slaughtered. These facilities cannot accommodate as many buffalo as Fort Peck.

“No animals will enter the quarantine program this winter.

“Each winter, buffalo migrate outside the boundaries of Yellowstone, and either face capture and shipment-to-slaughter (442 animals last winter) or hunting by tribes utilizing treaty-secured rights (284 animals last winter).

“Because there is limited capacity in the facilities in and near the Park and a refusal to use the Fort Peck facilities to their full potential, more buffalo will be slaughtered this winter.

“ITBC’s solution of quarantine and translocation, the alternative nearly 30 years in-the-making, helps offset the number of buffalo killed for migrating outside of the Park’s invisible fences.

“The buffalo that consecutively test negative for brucellosis for years within the program are transferred to tribal lands to preserve their unique genetics and restore Tribal spiritual and cultural relationships.

“They are the descendants of the buffalo our Native ancestors lived with for centuries, and are honored and revered by the many nations with whom they find a home.”

Ervin Carlson, ITBC’s President for the past 17 years stated, “ITBC appreciates the efforts of the state of Montana in supporting quarantine operations and is deeply grateful to the US Department of Agriculture, Yellowstone National Park and to the Fort Peck Tribes for their dedicated partnership in accomplishing this mission.

“Finally, this moment would not be possible without our Member Tribes’ years of participation, support, and tireless work to ensure that buffalo and Native people are reunited to restore their land, culture, and ancient relationship across North America.”

Testing and Quarantine Continue

Before shipping the Yellowstone Park buffalo out to other tribes the Fort Peck tribes did a final quarantine testing.

It was an unforgettable bright August morning in the northeast corner of Montana.

Robbie Magnan, Game and Fish director for the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes, rose before dawn to round up and ease the 40 buffalo bulls into closer corrals near the loading chute.

“There’s always been a lot of hoops that we’ve had to jump through, and it’s something that we’ve just worked diligently for a lot of years to get this far for this happening today,” said Carlson.

“So today is real gratifying, just to be able to get some animals out of [the park] and to tribes alive.”

“We have a drum group out here. They’ll sing the prayer songs to send the buffalo safely to their new homes, that they travel safe and receive blessings and say goodbye for us, and we’ll send them on their way,” Jonny BearCub Stiffarm says.

You’ll notice here at this gathering that there’s some real little children. Buffalo will always have been a part of their lives,” BearCub Stiffarm says.

“And so for a lot of us older generation, to be able to see that circle become complete has really been meaningful.”

If you’re experiencing quarantine fatigue, these bulls can relate, their handlers say.

“These guys have been in there for years,” Magnan says. “Most of their life they’ve been in some type of quarantine.”

They endured two years of quarantine at Yellowstone National Park, where they started their lives, before being transferred to Fort Peck for final years of isolation and disease testing.

“But today is a good day, because they’ll go to a home where they’ll never have to be tested again,” Magnan says. “And they have the rest of their life to enjoy being a buffalo.”

Their new homes are as far from here as Kansas, Wisconsin and Alaska. It was to be the largest ever inter-tribal transfer of buffalo.

A semitrailer backs up to the chute to start the first ones on their journey.

It takes two hours and lots of commotion for a group of tribal Game and Fish employees, plus a handful of community volunteers, to coax the 2,000-pound bulls through the chute and onto the trailers.

The Cherokee continue to work with the Council, which awards surplus bison from national parks each year to its member tribes, and hopes to obtain another 25 or 30 cows.

The two young bulls, each between 1,000 and 1,500 pounds, were trucked over 1,000 miles to Delaware County, Oklahoma this week.

Both animals managed the stress of the trip well, said Cherokee Deputy Chief Bryan Warner. They were at first held separately from the others in the herd to be slowly introduced into the population.

The two bulls will put on hundreds more pounds each to reach their massive 2,000-pound adult size, and in the meantime they will find their place in the hierarchy among other bulls and eventually reproduce naturally among the herd, he said.

As descendants of the buffalo that once roamed free more than 100 years ago, the new genetics bring a lineage to the herd welcomed in more ways than one, he said.

“Yellowstone buffalo are significant to tribes because they descend from the buffalo that our ancient ancestors actually lived among, and this is just one more way we can keep our culture and heritage and history alive.”

“This partnership with the InterTribal Buffalo Council continues to benefit the Cherokee Nation by allowing the tribe to grow a healthy bison population over the last five years,” Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr said in a press statement.

“Historically, bison provided an essential food source for tribes. Every part of the bison was used for food, clothing, shelter, tools and ceremonial purposes. These newly acquired bison will help revive some ancient cultural traditions, as well as provide expanded economic opportunities for future generations of Cherokees.”

Although bison are associated more with the Great Plains tribes, wood bison once roamed the Cherokee lands and all along the Atlantic Coast. Prior to European colonization, the animals played a critical role for the Cherokee people as a vital food source.

Until 2014, the Cherokee had not raised bison for 40 years. After spending two or three years working with the InterTribal Buffalo Council, the tribe’s herd now has about 180 bison.

Robbie Magnan says all this hard work is worth it to restore an animal that was once the center of life for many tribes across the Great Plains and Mountain West.

Along with other long-time workers in ITBC he believes contemplating a herd of buffalo can bring Native tribal members a sense of peace, love and strength in dealing with life’s problems.

The ITBC and the Fort Peck Tribes say this is the first of many large inter-tribal buffalo transfers out of the quarantine program.

This winter, they plan to transfer 30 to 40 animals, an entire family group, to one lucky tribe that can prove it has the resources to care for them.

Come spring, the ITBC is expecting a new shipment of buffalo from Yellowstone National Park to the Fort Peck Reservation.

First published January 12, 2021 on Buffalo Tales and Trails

Intertribal Buffalo Council Restores Herds — and More — Part 1

December 13, 2025

Over and over delegates testify: As we bring the buffalo back to health, we also bring our own people back to health. And that’s what it’s all about.

by Francie M. Berg

Whether it is unique training opportunities, large scale restoration goals, more effective marketing or Native cultural issues, ITBC has worked with tribes to restore buffalo on tribal lands. Photo ITBC.

Over and over delegates testify: As we bring the buffalo back to health, we also bring our own people back to health. And that’s what it’s all about.

In February 1991, a meeting in the Black Hills of South Dakota, hosted by the Native American Fish and Wildlife Society, brought Native people from all four directions, as is traditional, to talk about a topic that concerned them all.

How can Indian tribes with experience raising buffalo help other tribes restore buffalo to their lands? Why is this important to us?

Representatives of each of 19 tribes—most of them from the Plains states—spoke of their desire to obtain or expand buffalo herds and grow them into successful, self-sufficient programs.

Many difficult and complex problems were involved that tribes and herd managers had faced alone—with mixed results.

Each tribe that desired buffalo needed to purchase or set aside enough suitable lands for year-around grazing or hay lands, fence that land with high, sturdy fences, and obtain buffalo—all expensive options.

Not all tribal members agreed with the value of such land use.

Next, they needed to manage the herd wisely, so if possible, the buffalo herd would be financially self-sufficient.

Growing the herd, with a healthy calf crop each year—so they produced enough meat for tribal and ceremonial uses and young stock for sale or expansion—was essential.

Furthermore, far beyond the economics of it, most buffalo enthusiasts expressed concerns that they inspire others—not merely to restore live buffalo to tribally-owned pastures across the United States—but that they restore them in ways compatible with their traditional spiritual and cultural beliefs.

Although some tribes and tribal members had engaged in production of buffalo for sale and/or for subsistence and cultural use, these activities were conducted by each individual tribe, with little or no collaboration between tribes.

Frequent droughts on the Plains brought unexpected set-backs.

Some managers were able to fill some needs, and not others. Some herds dwindled and ended. Many managers became discouraged at the high costs and seemingly slight benefits.

Yet, others succeeded well.

As the meeting ended, all representatives knew they wanted to continue the discussion and find ways to work together to help each other.

It was plain to all that an organization to assist tribes with their buffalo programs was sorely needed.

With hard work and dedication of the group, the US Congress was approached with the need to appropriate funding for tribal buffalo programs. That June, in 1991, Congress voted to provide funding and donate surplus buffalo from national parks and public refuges to interested tribes.

This action offered renewed hope that the sacred relationship between Indian people and the buffalo might not only be saved but would in time flourish.

The intertribal group agreed to supervise federal grants and distribution of the animals.

Buffalo began coming home to reservations in earnest.

The Tribes again met in December 1991 to discuss how the Federal appropriations would be spent.

At this meeting, each tribe spoke of their plans and desires for buffalo herds and how to help existing tribal herds expand and develop into successful, self-sufficient programs.

In April of 1992 tribal representatives gathered in Albuquerque, NM.

It was at that meeting that the InterTribal Buffalo Council (initially called the InterTribal Bison Cooperative—ITBC)—officially became a recognized tribal organization. Officers were elected and began developing criteria for membership, articles of incorporation and by-laws.

In September of 1992, ITBC was incorporated in the state of Colorado and that summer established a permanent office in Rapid City, South Dakota.

“Having the buffalo back helps rejuvenate the culture,” says Jim Stone, Rapid City, Executive Secretary of the Intertribal Buffalo Council and a Yankton Lakota.

“In my tribe, like others, the buffalo was honored through ceremony and songs. There were buffalo hunts and prayers to give thanks to the buffalo.”

The council has adopted the mission of “Restoring buffalo to Indian Country, to preserve our historical, cultural and traditional and spiritual relationship for future generations.”

Thirty years of Tribal Buffalo Progress

Today, 30 years later, 69 federally recognized Tribes from 19 states have joined the Intertribal Buffalo Council. Most of these tribes own a buffalo herd, for a total of more than 20,000 buffalo living in tribal herds across the United States today.

Sixty-nine Tribes with ITBC herds in 19 states are divided into 4 regions with over 20,000 buffalo—most are west of the Mississippi River. ITBC.

InterTribal Buffalo Council Member Tribes

Alutiiq Tribe of Old Harbor

Blackfeet Nation

Cheyenne Arapaho of OK

Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe

Chippewa Cree Tribe

Cochiti Pueblo

Comanche Tribe of OK

Confederated Salish & Kootenai

Confederated –Tribes of the Umatilla

Crow Tribe

Crow Creek Sioux Tribe

Eastern Shoshone

Flandreau Santee Sioux

Fort Belknap Indian Community

Fort Peck Tribes

Ho-Chunk Nation

Iowa Tribe

Jicarilla Apache

Kalispel Tribe

Lower Brule Sioux Tribe

Mesa Grande Band of Mission Indians

Miami Tribe of OK

Modoc Tribe of OK

Nambe Pueblo

Nez Perce Tribe

Northern Arapaho

Northern Cheyenne

Omaha Tribe of NE

Oneida Nation of WI

Osage Nation

Picuris Pueblo

Pit River

Pojoaque Pueblo

Ponca Tribe of NE

Prairie Band Potawatomi

Prairie Island Dakota Community

Quapaw Tribe of OK

Rosebud Sioux Tribe

Round Valley Tribe

Ruby Tribe

Salt River Pima

Sac & Fox of Mississippi

San Juan Pueblo

Sandia Pueblo

Santee Sioux Tribe

Seneca-Cayuga of OK

Shawnee Tribe

Shoshone-Bannock Tribes

Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate

Southern Ute Tribe

Spirit Lake Sioux Tribe

Spokane Tribe

Standing Rock Sioux Tribe

Stevens Village

Taos Pueblo

Tesuque Pueblo

Three Affiliated Tribes

Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa

Ute Indian Tribe

Winnebago Tribe

Yakama Nation

Yankton Sioux Tribe

ITBC is committed to helping each tribe bring buffalo herds on Indian lands in a manner that promotes cultural enhancement, spiritual revitalization, ecological restoration and economic development.

Many are Plains tribes with a long history of dependence on buffalo for food, shelter and clothing.

Others have no known history of hunting buffalo, but desire the cultural experience.

“Today’s resurgence of buffalo on Tribal lands, largely through the efforts of the InterTribal Buffalo Council, signifies the survival of the revered buffalo culture as well as survival of American Indians and their culture,” says Ervin Carlson, Blackfeet, President of ITBC.

Ervin Carlson, president of ITBC, member of the Blackfeet tribe in northwestern Montana, recently stated their goal this way:

“For Indian Tribes, the restoration of buffalo to Tribal lands signifies much more than simply conservation of the national mammal.

“Tribes enter buffalo restoration efforts to counteract the near extinction of buffalo that was analogous to the tragic history of American Indians in this country.” In other words, they see the two tragic events as similar and parallel to each other.

“Today’s resurgence of buffalo on Tribal lands, largely through the efforts of the InterTribal Buffalo Council, signifies the survival of the revered buffalo culture as well as survival of American Indians and their culture.”

“We have many cultural connections to the buffalo,” says Alvah Quinn, a Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate from South Dakota, former manager of the tribal buffalo program.

“I grew up hearing about the buffalo, but we didn’t have any around on the reservation.’

His tribe’s last recorded buffalo hunt was in 1879.

Quinn says he will always remember the night in September 1992 when he helped bring the first 40 buffalo to his home reservation.

“I was really surprised that night. There were 60 tribal members waiting in the cold and rain to welcome the buffalo back home. After a 112-year absence!”

They now own 350 buffalo—one of many success stories.

After three decades, Intertribal Council leaders are even more convinced of the value of these buffalo herds.

Daily they are reminded that buffalo represent the spirit of native people and how their lives were once lived, free and in harmony with nature.

They’ve seen how bringing buffalo back to tribal lands helps to heal the spirit of Indian people.

Today some tribes own very large buffalo herds, for commercial as well as cultural purposes.

The Crow Tribe has 2,000 buffalo running free-range on their large, mountainous reservation spanning the state line between Billings, Montana, and Sheridan, Wyoming.

Pauline Small on horseback, carries the flag of the Crow Tribe of Montana. As a tribal official, she is entitled to carry the flag during the Crow Fair parade at Crow Agency, south of Billings, Montana. The Crow have one of the largest tribal herds, at 2,000 head.

At Pine Ridge, the Oglala Sioux raise 1,100 including both tribal and college buffalo herds, and Rosebud also raises 300 under a tribal umbrella, reports Stone.

Other tribes set goals for a small herd mostly for cultural and educational purposes, explains Mike Faith, long-time tribal buffalo manager and now tribal chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux, who also serves as Vice President of the Executive Council of the Intertribal Buffalo Council.

Mike Faith, Vice President of ITBC, Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairman and long-term manager of the tribal buffalo herd, advises “Quality over quantity is what counts.” ITBC.

Faith has worked with the InterTribal group since its beginnings. He says a new tribe might slaughter only one or two buffalo a year for special celebrations and ceremonial use.

It depends on land available, land uses on the reservation, tribal population and historic dependence on buffalo.

“Quality over quantity is what counts,” says Faith. “Whether they want a small herd—20 or 30—or a larger commercial herd, we can give help and technical assistance.”

No matter the numbers, Faith suggests it is important that new tribes take their buffalo venture seriously. Hiring a knowledgeable buffalo manager is critical.

The Intertribal Council offers training and educational programs and coordinates transfer of buffalo and grant funds.

Troy Heinert, ITBC Range Technician, visits Rosebud, SD, helping Wayne Frederick and his crew work 2014 surplus bison “on hold” so they can be released out into the pasture. ITBC, Facebook, October 31, 2014.

Experts are available to help tribal leaders work out management and marketing plans that fit their particular concerns and goals, if desired.

Details like building high, strong fences before the buffalo arrive are essential—and costly.

Big bulls can jump six feet or more.

Round or angled corrals work better than square, as buffalo tend to jump when they hit a corner.

They may get hung up and die of a heart attack.

Corrals work best when built with sorting tubs and alleyways with enclosed sides so animals move ahead without seeing out. Curved alleyways are helpful so buffalo think moving ahead is a way to escape.

There may be grants available to help defray costs, the experts tell the tribes.

A buffalo herd needs plenty of space, grass and water. On request, experienced leaders will visit to help determine goals and advise on land base.

Sometimes they recommend reducing animal numbers to better accommodate the land available.

They also work with federal agencies to help bring fractured lands together.

A manager with training in low-stress buffalo handling is preferred.

Handlers familiar with raising cattle will find surprising differences, Faith explains.

For instance, many cowboys shout at their cattle when chasing them.

But buffalo are essentially wild animals, he says. They feel stressed with noise and pressure, so it’s better to move them quietly and slowly.

Arnell D. Abold, of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux) Tribe, was recently appointed to the position of the Executive Director for the InterTribal Buffalo Council. Ms Abold is the first Native woman to serve as Director of ITBC since its inception in 1992.

Arnell D. Abold, of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux) Tribe, serves as Executive Director for the InterTribal Buffalo Council. The first Native woman Director of ITBC since its inception in 1992, she has served as its Fiscal Director since Nov. 2001. ITBC.

Ms. Abold previously served as the Fiscal Director. She continues to devote her career to the vision and the mission of the organization.

Her passion, belief, and devotion to the buffalo and the membership tribes that hold the buffalo sacred is what drives her dedication and loyalty to the organization.

Tribal Buffalo Success Stories

One of the first tribes to raise buffalo, the Taos Pueblo, in northern New Mexico in the valley of a small tributary of the Rio Grande, obtained them in 1902 or 1903 from the Goodnight herd, according to Jim Stone, of the ITBC.

The Salish-Kootenae had buffalo too, perhaps descended from the original calves brought by Samuel Walking Coyote to the Montana Flathead reservation.

On South Dakota Indian reservations, the Pete Dupree and Scotty Philip families continuously raised buffalo from the wild in the 1880s.

Some early private buffalo herds did not survive long or were removed during the brucellosis eradication program, says Stone.

Most replacement buffalo now come from the federal park system and have been disease-free for decades.

The Yakama herd grew from 12 buffalo in 1991 to more than 200, producing 40 to 50 calves every year. The tribe, located in south central Washington on the Columbia Plateau, hopes to expand its buffalo herd to 400 over the next few years, and furnish more meat for tribal elders and low-income families.

Eventually the Stillaguamish Tribe near Arlington, Washington plans to share buffalo meat with neighboring tribes and make it available to the general public.

ITBC Buffalo herd arrives at new home in Montana. Photo fwp.mt.gov.

In 1997, the Oneida Tribe of Wisconsin started their buffalo herd with 13 heifers and a bull from Wind Cave National Park.

When she saw the delighted response of Native People on western reservations to the return of buffalo, Pat Cornelius, now Oneida herd manager and former board member of the Intertribal Bison Cooperative, felt sure her people would be heartened as well by a herd of their own.

She describes the arrival of the first 14 buffalo as an awesome spiritual moment.

“The earth shook!” she said, when the animals jumped from trucks.

By 2007, the Oneidas owned 120 cows and bulls, with 43 calves.

The presence of buffalo has made a big difference to them, Cornelius says, describing the many local people visiting daily in summer and winter from a specially-built viewing mound and shelter.

The Eight Northern Pueblo tribes of New Mexico, like many other Native Americans, live on the land of their ancestors. Five maintain buffalo herds and cooperate to diversify bloodlines.

The Picurís herd began over a decade ago with one female and one bull. It has grown to 80 head, not including spring calves.

Their buffalo are pastured in a field close to the road, so visitors often stop.

Tribal herd manager Danny Sam cautions them that it is not safe to walk among the buffalo.

Sam serves as secretary for the Intertribal Buffalo Council and has been involved with the program since the beginning.

He has seen many changes. One he does not care for is that federal inspections, taken over from the state, require more paperwork, charge a fee and classify buffalo as an exotic species, rather than livestock.

“They’re not an exotic species,” Sam says. “They’re native to this country.”

New Bison Herds in Alaska

Alaska may not seem like a natural home for buffalo. But bones and petroglyphs prove the larger wood buffalo lived and were hunted there in ancient times.

The first Alaskan group to join the restoration program, after Athabascan tribes began introducing plains buffalo, was at Stevens Village near Delta Junction.

The new herd there includes 38 buffalo, 14 of them calves, obtained with help from the Intertribal Buffalo Council.

Rocky Afraid of Hawk, a Lakota Oyate elder and the Council’s spiritual advisor, flew to Alaska from South Dakota for a welcoming ceremony.

He told the Athabascan people that buffalo were placed on earth to teach people how to live.

“You can learn from them.” he said.

Afraid of Hawk presented the village with a buffalo skull to use in ceremonials and prayers. To bless the event, he burned sagebrush in a metal can with coals from the fire.

Randy Mayo, first chief of the Stevens Village tribal council, carried the smoldering sage to guests and let them wave smoke over their faces.

The village presented Afraid of Hawk with tobacco and salmon strips.

Traditional chief David Salmon, a Chalkyitsik elder, sat on a folding chair beside a wood fire, relating buffalo stories told by his grandfather.

Beside him, Herb George, a Stevens Village tribal council member, stirred a bubbling soup made with buffalo meat.

He said he was making soup the way his father taught him—like a traditional potlatch soup, but with buffalo bones instead of moose.

Mayo believes being around the buffalo can help people work through their problems.

He acknowledged that when the village voted to move forward with raising buffalo, he didn’t know much about the animal that had provided food, clothing and shelter to his ancestors.

He has learned a lot.

“Every time I come here it lifts me up,” said Mayo. “Just observing them, you never get tired of it.”

Stevens Village leaders encouraged other Athabascan villages to start their own buffalo herds.

A Holistic Approach at InterTribal Buffalo Council

Lisa Colome, Technical Service Provider for the Intertribal Buffalo Council in Rapid City, served as rangeland specialist, but like others who work there, she takes a holistic approach.

A Cherokee elder who came from Oklahoma for training told her of their first herd.

“I can’t tell you what it meant to us,” he said. “I really believe with the return of the buffalo there’ll be an awakening of our people.”

Teaching young people about traditional relationships and spiritual connections to the buffalo is important to Colome. “This is what tribes are seeking.”

Teaching buffalo values to children are important to Indian tribes. Young people have a natural awe of buffalo, reports Lisa Colome, Technical Service Provider at ITBC headquarters in Rapid City, SD.

“Native kids have a natural connection to the buffalo,” she says, her dark eyes warming.

“They’re just naturally born with this awe. They are never disrespectful and show genuine caring.”

She enjoys bringing children to see the buffalo.

“Once I brought a group of sixth graders. They watched silently as the buffalo ran over the hill out of sight. I said, ‘Just wait, I think they’ll come back if we’re quiet.’

“We peeked over the hill. The buffalo circled back and came within 25 feet. The kids had never been that close before.”

It’s easy to see that Colome is excited about her work, whether her day focuses on herd and forage health, or cultural and spiritual ties. Not always do tribal herds bring financial benefits, she knows—often quite the opposite. But always she sees cultural value.

‘I love being a part of developing tactics, plans and solutions that ensure buffalo are here for generations to come,” she says.

“Return of the buffalo awakens the native spirit—it gives us hope of better lives.”

First published December 29, 2020 on Buffalo Tales and Trails

15 Facts About Our National Mammal: The American Bison

November 8, 2025

The American Bison was named the national mammal of the United States on May 9, 2016. This majestic animal joins the ranks of the Bald Eagle as the official symbol of our country—and much like the eagle, it’s one of the greatest conservation success stories of all time.

Written by Francie M. Berg

Department of Interior 5/9/2016

The American Bison was named the national mammal of the United States on May 9, 2016. This majestic animal joins the ranks of the Bald Eagle as the official symbol of our country—and much like the eagle, it’s one of the greatest conservation success stories of all time.

In prehistoric times, millions of bison roamed North America—from the forests of Alaska and the grasslands of Mexico to Nevada’s Great Basin and the eastern Appalachian Mountains. But by the late 1800s, there were only a few hundred bison left in the United States after European settlers pushed west, reducing the animal’s habitat and hunting the bison to near extinction. Had it not been for a few private individuals working with tribes, states and the Interior Department, the bison would be extinct today.

Explore more fun facts about the American bison:

1. Largest mammal in North America

Bison are the largest mammal in North America. Male bison (called bulls) weigh up to 2,000 pounds and stand 6 feet tall, while females (called cows) weigh up to 1,000 pounds and reach a height of 4-5 feet. Bison calves weigh 30-70 pounds at birth.

Bison at Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge in Colorado. Photo by Jim Carr, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

2. Department of Interior Stewardship

Since the late 19th century, Interior has been the primary national conservation steward of the bison. Public lands managed by Interior support 17 bison herds — or approximately 10,000 bison — in 12 states, including Alaska.

A bison calf walks between two adults. Photo by Rich Keen, DPRA.

3. Bison vs Buffalo

What’s the difference between bison and buffalo? While bison and buffalo are used interchangeably, in North America the scientific name is bison. Actually, it’s Bison bison bison (genus: Bison, species: bison, subspecies: bison), but only saying it once is fine. Historians believe that the term “buffalo” grew from the French word for beef, “boeuf.”

A resting bison at Wichita Mountains National Wildlife Refuge. In 1907, the American Bison Society and the New York Zoological Society donated 15 bison to the Wichita Mountains National Wildlife Refuge in Oklahoma. Today the refuge’s herd includes an estimated 650 bison. Photo by Nils Axelsen.

4. Yellowstone National Park Only Place Continuously Lived*

Yellowstone National Park is the only place in the U.S. where bison have continuously lived since prehistoric times. What makes Yellowstone’s bison so special is that they’re the pure descendants (free of cattle genes) of early bison that roamed our country’s grasslands. As of July 2015, Yellowstone’s bison population was estimated at 4,900—making it the largest bison population on public lands.

A bison walking by the Grand Prismatic Spring at Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. Photo by Jennifer Michaud.

5. Baby Bison called “Red Dogs”

What’s a “red dog”? It’s a baby bison. Bison calves tend to be born from late March through May and are orange-red in color, earning them the nickname “red dogs.” After a few months, their hair starts to change to dark brown and their characteristic shoulder hump and horns begin to grow.

A bison and calf at Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge in Colorado. Photo by Rich Keen, DPRA.

6. Bison and Native Americans are Intertwined

The history of bison and Native Americans are intertwined. Bison have been integral to tribal culture, providing them with food, clothing, fuel, tools, shelter and spiritual value. Established in 1992, the InterTribal Buffalo Council works with the National Park Service to transfer bison from national park lands to tribal lands.

The National Bison Range in Montana. Photo by Ryan Hagerty, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

7. Watch Bison’s Tail for Warning

You can judge a bison’s mood by its tail. When it hangs down and switches naturally, the bison is usually calm. If the tail is standing straight up, watch out! It may be ready to charge. No matter what a bison’s tail is doing, remember that they are unpredictable and can charge at any moment. Every year, there are regrettable accidents caused by people getting too close to these massive animals. It’s great to love the bison, but love them from a distance.

A bison watching over a calf at Yellowstone National Park. Photo by Diana LeVasseur

8. Wind Cave National Park Herd Started New Herds

Wind Cave National Park’s herd helped revive bison populations around the country. The story starts in 1905 with the formation of the American Bison Society and a breeding program at the New York City Zoo (today, the Bronx Zoo). By 1913, the American Bison Society had enough bison to restore a free-ranging bison herd. Working with Interior, they donated 14 bison to Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota. More than 100 years later, the bison from Wind Cave have helped reestablishing other herds across the United States and most recently in Mexico.

A small herd of bison at Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota. Photo by Tim Ehrlich.

9. Bison look Lazy but don’t be Fooled

Bison may be big, but they’re also fast. They can run up to 35 miles per hour. Plus, they’re extremely agile. Bison can spin around quickly, jump high fences and are strong swimmers.

A bison charging through a river at Yellowstone National Park. Photo by Donald Higgs.

10. Buffalo eat Grass, Weeds, Browse

Pass the salad, please. Bison primarily eat grasses, weeds and leafy plants—typically foraging for 9-11 hours a day. That’s where the bison’s large protruding shoulder hump comes in handy during the winter. It allows them to swing their heads from side-to-side to clear snow — especially for creating foraging patches. Learn how bison’s feeding habits can help ensure diversity of prairie plant species especially after a fire.

Bison in the snow at Yellowstone National Park. Photo by Neal Herbert, National Park Service.

11. President Teddy Roosevelt Helped save Bison

From hunter to conservationist, Teddy Roosevelt helped save bison from extinction. In 1883, Teddy Roosevelt traveled to Dakota Territory to hunt bison. After spending a few years in the west, Roosevelt returned to New York with a new outlook on life. He paved the way for the conservation movement, and in 1905, formed the American Bison Society with William Hornaday to save the disappearing bison. Today bison live in all 50 states, including Native American lands, wildlife refuges, national parks and private lands.

A bison stands alone in Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota. Photo by Brad Starry.

12. Average Lifespan 10 to 20 Years

Bison can live up to 20 years old. The average lifespan for a bison is 10-20 years, but some live to be older. Cows begin breeding at the age of 2 and only have one baby at a time. For males, the prime breeding age is 6-10 years. Learn how Interior works to ensure genetic diversity and long-term viability of bison.

Bison herd on the move. Photo by Neal Herbert, National Park Service

13. Buffalo Enjoy a Wallow

A little dirt won’t hurt. Called wallowing, bison roll in the dirt to deter biting flies and help shed fur. Male bison also wallow during mating season to leave behind their scent and display their strength.

A bison rolling around in the dirt of a wallow. Photo by Jim Peaco, National Park Service.

14. Ancient Bison came from Asia

The American bison’s ancestors can be traced to southern Asia thousands of years ago. Bison made their way to America by crossing the ancient land bridge that once connected Asia with North America during the Pliocene Epoch, some 400,000 years ago. These ancient animals were much larger than the iconic bison we love today. Fossil records show that one prehistoric bison, Bison latifrons, had horns measuring 9 feet from tip to tip.

Bison standing in the snow at the National Elk Refuge in Wyoming. Photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

15. Bison have Poor Eye Focus